Lyudmila Veniaminovna Belgorodskaya – professor, Siberian Federal University (Krasnoyarsk, Russia)

Nikolay Ivanovich Drozdov – professor, Siberian Federal University (Krasnoyarsk, Russia)

Vita Vitalievna Vonog – associate professor, Siberian Federal University (Krasnoyarsk, Russia)

The American Fate of the Chinese Collection of G.V. Yudin, Krasnoyarsk Merchant-Bibliophile

Keywords: G.V. Yudin`s documentary collection, Russian Album of China, Library of Congress, L. S. Igorev, Russian artists in China, ethnography of China, XIV the Russian Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission in China.

Abstract. The article is devoted to the art collection study on the ethnography of China based on the collection of G. V. Yudin, a merchant-bibliophile. The paper states the reasons for the collector’s interest in Chinese themes, as well as the reasons for compensating lacunae in the collection formation and classifying its part division.

Nowadays, a collection of 333 drawings and sketches, entitled "Russian drawings of China," is in possession of the Department of Photography and Engravings of the Library of Congress. The theme of images has been identified and classified, the time of creating images has been determined. The major part of the images is found to have been made in China and reflected the traditional way of life already affected by the processes of Westernization. Particular attention is paid to the argumentative issue concerning image authorship.

The authors of the paper state the hypothesis that the collection was made by a group of Russian and Chinese artists, the images were not created at the same time but in terms of broad chronological frames of the latter half of the XIX century. Part of the drawings was most likely painted by L. S. Igorev, an artist of the 14 Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission in Beijing. "Species from a bird’s eye view" may belong to the topographer Shimkovich. The issue concerning the existence of visual images of Yudin ethnographic collection abroad nowadays has been studied.

The current growth of political and scientific interest in the history of bilateral relations between Russia and China makes it relevant to study the issue of how the Chinese theme is represented in Russian books and art collections. Nowadays in Russia, the research entitled "China in the works of Russian artists of the XVIII-XIX centuries (the role of visual images in the history of cultural interaction)" under the auspices of St. Petersburg University is being carried out. Its project manager is N. A. Samoilov, a professor of the Eastern Faculty of St. Petersburg State University, a head of the department. Group members are V. S. Myasnikov (an academician, a doctor of History, a professor, a head of the department of Institute of Scientific Information for Social Sciences RAS), G. N. Goldovsky (a head of the department of painting of the XVIII–early to mid XIX century of the State Russian Museum), as well as the other scientific and museum workers. The group discovered previously unknown collections of Chinese drawings in the collections of Russian and Historical Museums. New materials were found with the exception of L. S. Igorev who worked among four artists as part of the Russian Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission in China. We can agree with the opinion of N. A. Samoilov, a project manager, who wrote in the article devoted to preliminary results of the work on the topic, "In addition, it is quite obvious that the range of available paintings and drawings is much wider and is not limited to those ones that are presented in the above-mentioned museums" [Samoilov 2016 p.39]. The author notes that Russian art collections on Chinese themes have been found even in Canada. However, we found that visual evidence of Russian-Chinese artistic links is stored even in the United States.

Among book and documentary collections assembled by private individuals in pre-revolutionary Russia, the book, art, and documentary collection of Gennady Vasilyevich Yudin (1840-1912), a successful merchant-bibliophile, Krasnoyarsk citizen, stands out for its wealth and complex fate. The first collection at the time of sale counted 80,000 books (according to some sources, this number corresponds to about 100,000) and about 500,000 items of documentary materials. It turned out to be the largest and most valuable private library in pre-revolutionary Russia. For a number of reasons, including family, finances, and fear for the fate of the collection in the context of the beginning of the revolution, it was sold to the Library of Congress in 1906. In 1907, the book collection and a small part of the manuscript collection (mainly on Russian-American relations) were delivered to Washington, where most of the collection is currently stored. Then, G. V. Yudin assembled the second collection, which is now stored mainly in Moscow and Krasnoyarsk.

The historiography of the Yudin collection is very extensive, including monographic studies, collections of documents, as well as the conference "Yudin Readings" held in 1990, 1992, 2000, 2004, 2007, 2010, 2020. In 2012 and 2015, the conference "Yudin Readings" was held in Krasnoyarsk, materials of which were presented in several conference proceedings [Eighth... 2015]. In 2018, Siberian Federal University published a book accompanied by comments from Siberian historians about the circumstances concerning the sale of the famous collection. American bibliographers also made a great contribution to Yudin's studies. For example, not so long ago, American bibliographers discovered correspondence between US President Theodore Roosevelt and two Library directors about the feasibility of purchasing the collection of the Siberian entrepreneur [Laich 2013].

The authors of this publication have established that G. V. Yudin was always affected by a mysterious eastern country. Having reached advanced age, he invited the reporter A. A. Titov to go with him to the Far East, and then go to mysterious Harbin. These plans didn’t come true. Currently, Krasnoyarsk has 13 fundamental works on the history of China and 17 books on the geography of the country from the merchant’s second library assembled in time frames 1906–1912. [Yudin collection dated 2004, № 184–194, p.206; Yudin collection dated 2006, № 454–466]. A huge fund of literature on Chinese themes was found in 1907 across the ocean.

Prints, lithographs, and drawings from the Yudin collection in the Department of Copying and Photographs of the Library of Congress are of particular interest to historians. We are talking about 333 drawings assembled in one album, collectively called by researchers "Russian drawings of China." The collection is microfilmed, digitized; information about the images is available free of charge, and a significant part of the visual images (51 items) is posted on the Library of Congress website. This collection has not been studied by any historians, bibliographies, or historians of painting. This allows researchers to explore many mysteries of the art collection.

The latest direction of scientific historical research takes place in the field of source reading of visual sources. We were not interested in the actual artistic characteristics and merits of the images. For historians, other meanings of visual sources were important: identifying the views of China, analyzing the images of the everyday life of its inhabitants, and studying the issue concerning the features of reflecting the realities of everyday life in China through the eyes of Russians in the latter half of the XIX century.

This publication is aimed at evaluating the composition of this image collection, classifying images by subject, establishing the authorship of the drawings, identifying the depicted historical and natural objects, studying the history of images based on the Yudin collection in the XX – early XXI century.

The images of the "Russian Album" are made using different techniques: the artists (or an artist) used ink, a pencil, tempera, charcoal, and watercolors. Most of the drawings are in black and white, and there are a few color images in the collection. Some black-and-white images are partially colored by the artist. The dimensions of the drawings are non-standard and not repeated; on average, they are smaller or slightly larger than the current standards A6 (105x148) and A4 (210x270). Here are the options for the sizes of images stored in the library: 11,9x7,3; 19x33,8; 15x22,5; 24,3x32,3; 25,7x33; 21,2x26,7; 20x17,2. The image dimensions are never repeated. The works are made on Chinese paper. For the most part, the visual material can be evaluated as sketches for future paintings. Some images contain texts and notes in Russian and Chinese. Chinese inscriptions are mostly presented to the right and left of the image. Data about the presence of Russian markings are given by the Library of Congress bibliographers in the descriptions, but the texts themselves are not given. The library specialists described the content of the images in detail. As an example, here is the name of one of the drawings: "A street scene, possibly near a temple, with figures of adults and children, some greeting each other; a street barker is depicted on the right; two pigs are depicted on the background."

The staff of the Library of Congress attributed the time of drawings to time intervals beginning in 1860 and ending in 1900 or 1910. The lower time frame is probably related to the signing of the Beijing Treaty between Russia and China. The border between Russia and the Qing dynasty was established along the Amur, the Ussuri, and the Sungari rivers. Russia received the right to duty-free trade along the entire eastern border. Economic and cultural contacts between the two countries began to materialize more widely in the creation of documentary and artistic images of the neighboring country. In addition, the Europeans in the drawings are depicted in the uniform of the 1850s and 60s, the time referred to the armed conflict between China, France, and Great Britain during the Second Opium War.

Since the year of collection sale is known exactly, the upper time frame stated in the American version of attribution is disputable; it should be limited to at least 1906. The option of specifying the execution of a number of images before 1900 seems to us convincing, at least in relation to some of the works. The fact is that in the sketches and drawings presented in the album, there are views of several Christian churches in Beijing in the form in which they existed until the end of the XIX century. During the riots in 1900, caused by the Boxer Rebellion, the cathedrals burned down. The current buildings of the temples were built in the XX century.

By now, the exact history of the creation and the circumstances of the appearance of the album in the collection of the Krasnoyarsk merchant have not been clarified. We have established that on the back cover of the album, there is a marking of V. I. Klochkov, a famous bibliophile, antiquarian, publisher, and bookseller. Due to the active participation of this St. Petersburg antiquarian, the library of G. V. Yudin was collected.

It is known that Gennady Vasilyevich Yudin was very pedantic. From the age of thirteen, he kept copies of letters, theater tickets, posters, receipts, notes, and kept daily income and expense records. He kept this habit until the last days of his life. Yudin kept all his papers in complete order. It is difficult to assume that the information about the collection purchase was not reflected in the documents of personal origin. The bibliographer and historian I. Polovnikova found that in Krasnoyarsk, the employee P. A. Shilkov described archival documents for five years according to G. V. Yudin's instructions. By 1907, the manuscript was 7,150 pages long. The catalog, as well as the other reference books from the archive, was not sent overseas. But after the revolution, these manuscripts disappeared. The description of the state of the Krasnoyarsk part of the archive at the time of its transportation to the museum (1923) was terrible: the doors were broken in the building; papers, broken frames, torn engravings were on the floor; some folders fell on the road during the delivery, they were picked up by ever-present boys [Polovnikova 2010 p. 268]. The description of circumstances of album purchase by the merchant is likely to have disappeared during these years.

LC (Library of Congress) employees attributed the images to drawings made in Siberia and Mongolia. This is probably partly true in reference to a small group of images so-called "Russian views," "Russian carts representing part of a caravan, with yurts on the right and mountains in the background," "Interior of a western-style house, possibly a Russian border post with western paintings on the walls." Mongolian views are represented by the drawing "Houses with paper windows and a Mongolian yurt in the front garden." However, the vast majority of images represent views of China. This is indicated by recognizable architectural objects and historical landscapes of the country.

The subject matter of images of China can be divided into several groups. The first group is the smallest one, and it can be called "Nature of the country." It includes images of the natural landscapes and wildlife of China.

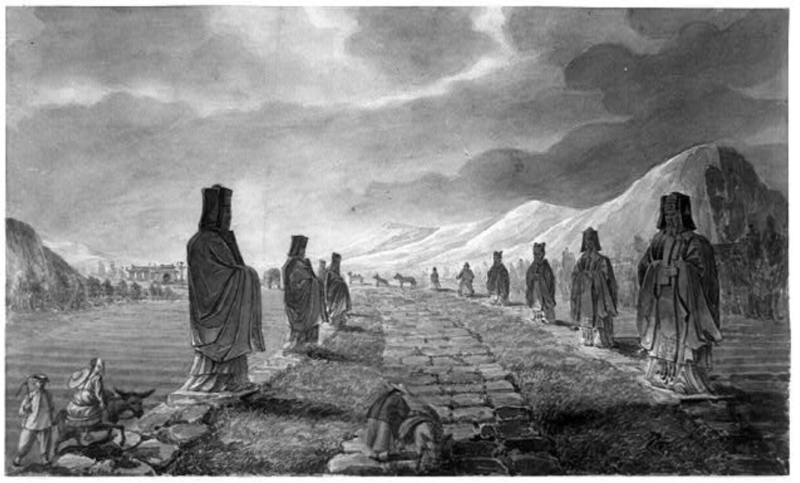

The second group, which can be collectively called "Historical and architectural views of the country," presents images of palaces, bridges, Buddhist temples, pagodas, arches, and engineering structures of the country. We are talking about the drawings of the Beijing Palace where "the emperor met the ministers every morning," the drawing "A boy leading a donkey with a woman sitting on it, near a section of the Great Wall outside Beijing," "A bird’s-eye view of the Mukden Palace." The artistic image gives an idea of the beautiful Mukden Palace-the residence of the first emperors of the Manchu dynasty in Shenyang.

The album’s pages depict various Buddhist temples, pagodas, and majestic arches. The image of the arched bridge has artistic accuracy and expressiveness. The pencil drawing, called by the LC staff "A high-arched bridge over the river," probably reproduces the introduction of the Yudaqiao Bridge (the Moon Bridge) built in the XVIII century on the territory of the Summer Imperial Palace. Images of Christian churches, both Orthodox and Catholic, deserve special attention. The identified image of St. Joseph’s Cathedral, a Catholic cathedral in the center of Beijing, is of historical value. The fact is that the temple was built in 1653; in 1720, it was destroyed by an earthquake; and later, it was restored. In 1807, the church burned down and was built again in 1884. But this building was repeatedly burned down in 1900 during the riots during the Boxer Rebellion.

The authors of the article identified the image in one of the album drawings of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Beijing in the form in which it existed before 1900 according to other original types of cathedrals that have come down to us. According to clearly identified images that have come down to us, the Northern Courtyard of the Russian Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission can be clearly recognized in the image "A bird’s-eye view of the walled church in Beijing."

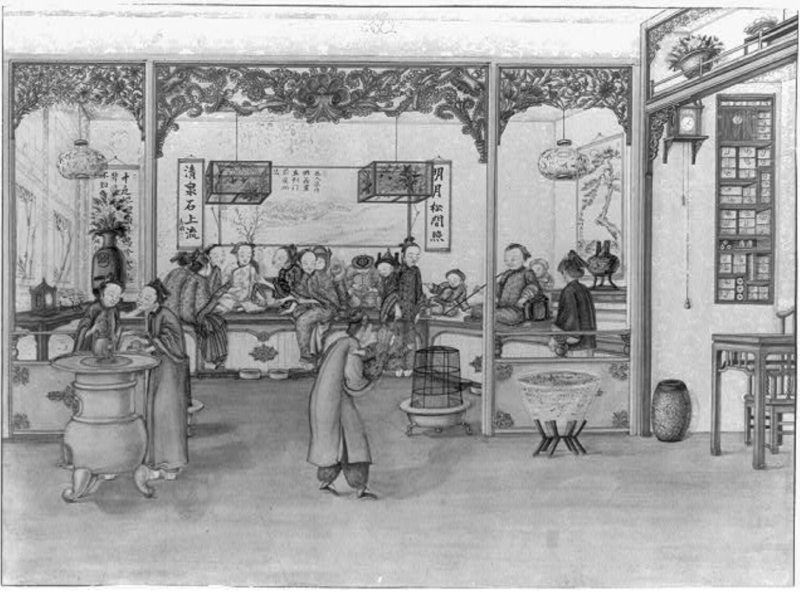

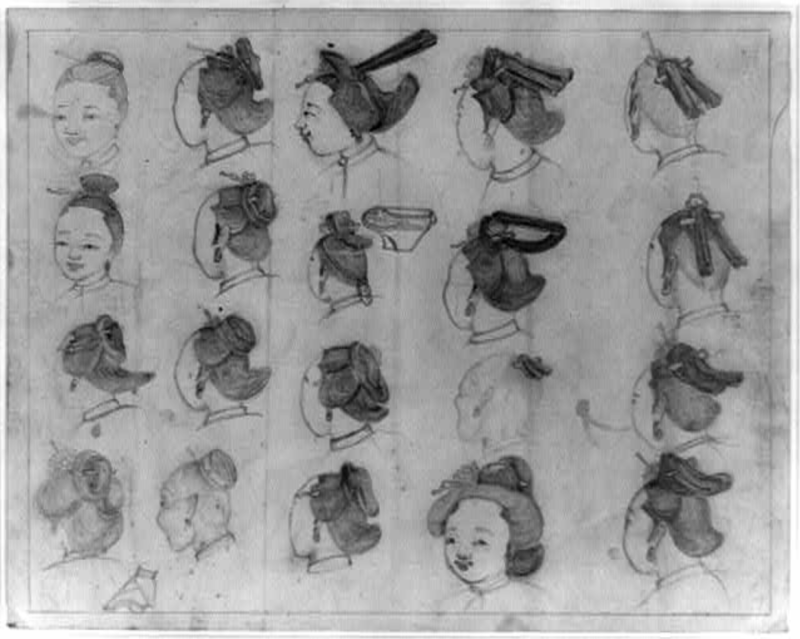

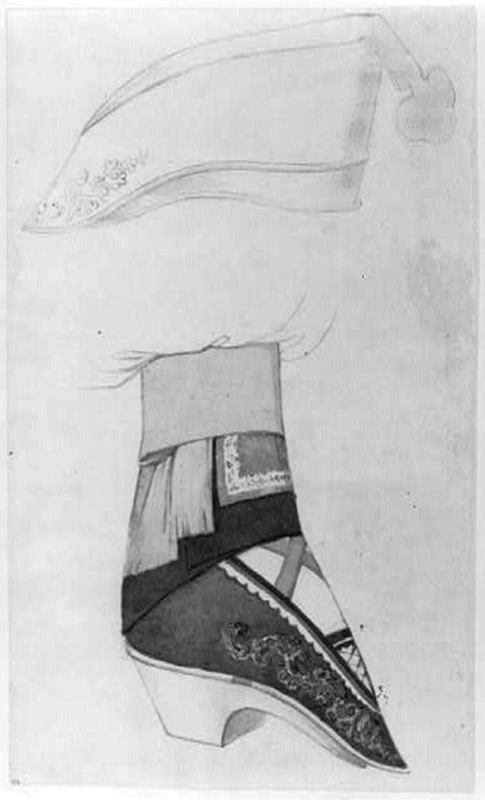

The third group of images can be called "Portraits and genre scenes." It includes male portraits (of nobles and commoners), visual images of family groups, drawings of children, genre scenes on the streets of cities, and ones depicted in the interiors of various public spaces. The officials are depicted with hand fans, seriously, and with a sense of dignity posing for the artist. The drawing with twenty women’s heads shows a variety of options for national hairstyles (Chinese women’s hairstyles and faces). There are several drawings of deformed female legs in the album, which the Chinese called "golden lotuses." The images of the album also give an idea of special miniature women’s shoes – "lotus shoes."

Most of the images reflect the life of traditional China, which has not been seriously affected by the modernization processes. Everyday agricultural labor is represented in the sketch "The Chinese are engaged in various types of labor: harvesting, deforestation, planting rice, carrying load."

The images allow us to create an accurate representation of everyday life, forms of rest, and activities of the Chinese in the latter half of the XIX century. The drawing "Chinese primary school classroom with teacher, smoking a long pipe, and students, includes Chinese language characters” represents students kneeling in punishment for not doing homework or violating discipline, a sketch of "A lively street scene in Beijing" with accurately reproduced signs, giving grounds to identify them as "tea room" and "shop for selling alcohol." An example of a description of a city scene can be the following detailed description of the image, "The drawing shows a street scene in the city with officials or businessmen in the center, each of whom is carrying a stick with a rope on which hangs a cage with a bird. On the left are two women, one of them is wearing a fashionable kimono and high wooden shoes, the other one has her feet bandaged, smoking a long pipe. On the right there are four people dressed in rustic style, playing dominoes outside a tearoom or restaurant. Two animals are eating from a trough. The city gates are visible in the background." "Dancers or acrobats with cymbals and drums," "A street scene, possibly near a temple, with figures of adults and children, some greeting each other; a street barker is depicted on the right; two pigs are depicted on the background." The drawing "Chinese boys playing spinning tops" surprises the Russians by the fact that the children control the spinning top with a fairly long rope, and not with a vertical metal pin with a spiral thread, which is typical for the Russian top.

The part of drawings allows us to record the introduction of the first Westernized trends in the everyday way of life in Qing China. Genre scenes of the changing daily life of China are represented by the watercolor drawing "Celebration in a Chinese public house," where foreign objects are next to traditional household items: a wall clock with weights (weight-driven wall clock), a kitchen stove, a brazier with a supply of coal, a European bench. The drawings "A European named Juhn is depicted in Chinese clothes," "A lying spotted dog, possibly an English spaniel" also serve as markers of the country’s contacts with the Western world.

Researchers are faced with the question of the drawings and sketches' authorship and the circumstances of their creation. As for the American researchers, there are different estimates in their works. Some, quite clearly, do not correspond to historical reality. The work belonged to the famous American historian D. Mungello "The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800" (Mungello D. E. The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800. 4 ed. New York; Toronto; Plymouth, 2012), published in four editions, in the last edition, contains an illustration with a view of the Southern Cathedral, based on the analyzed album, indicating that the drawing was made by G. V. Yudin. It is obvious that the bibliophile only bought a collection of drawings and cannot be referred to the number of artists.

To clarify the information about the history of the album, the authors turned to Harold Laich, the largest expert on the Yudin collection at the Library of Congress. He was specially introduced to the album in the department of prints and photographs. The correspondence with X. Laich made it possible to learn that Robert Allen, who worked as a researcher in the European section of the Library of Congress (1951–1985), was studying the issue concerning the authorship of Chinese images. The result of the research was the Memorandum prepared by him in 1978, addressed to the head of the Department of Prints and Photographs of the LC J. Cooper’s "Possible origin of Chinese drawings based on Yudin Collection." The author believed that the drawings were probably made by someone from the participants of the 14th Russian Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission in Beijing. It is no coincidence that American bibliographers called the album "The Russian Album of China."

R. Allen suggested that the author of the drawings could be the artist Lev Stepanovich Igorev. Less likely, the participant of the mission is the doctor P. F. Kornievsky. Among the possible authors, R. Allen also named the military topographer Ya. G. Shimkovich. This information was not presented in publications and reports at conferences but remained a document "for official use" of the library staff. R. Allen relied on documentary evidence and materials that are not directly mentioned in the Memorandum. Let’s consider these versions as a working hypothesis.

Since 1978, new publications have appeared, and a new corpus of historical sources has been put into circulation. The artist L. S. Igorev and the doctor P. A. Kornievsky indeed belonged to part of the 14th Russian Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission (1858–1864). The historian E. E. Nesterova has researched new archival materials on the Russian Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission in Beijing and the beginning of Russian-Chinese contacts in the field of fine arts. The attention to the ethnographic themes of all four artists, who painted various types of China throughout the history of the Spiritual Mission to China, was dictated by State authorities. As early as 1825 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs addressed to the Academy of Fine Arts with a request to teach artists the Chinese language to work in the country. It was supposed to teach them the Chinese language, painting, portraiture, and the technology of analyzing the composition of Chinese paints. The President of the Academy of Fine Arts mentored artists who went to China, "You have to put into all your efforts to the study of making and using Chinese real water paints and other preparations of any kind," you have to "be permanently engaged in drawing from nature all kinds of unusual clothing and costumes, household goods, tools used in various crafts, musical instruments, weapons, horse harnesses for riding and for driving, buildings, various kinds of domestic or wild animals, trees, flowers, fruits, and so on and so forth," so that "everything visible and drawn is presented exactly as it is in nature, without decorating anything.... imagination" [Nesterova 1993 p. 130].

Lev Stepanovich Igorev (1821-22–1893-94) was a painter and an icon painter. He was born in Saratov province in a large family of a sexton. From the age of ten, he studied at Petrovsky Theological School in Saratov; in 1838, he continued his studies at Saratov Theological Seminary. After graduating from it, he entered St. Petersburg Theological Seminary, provided that after the necessary training, he received a position as a drawing teacher in one of the theological schools. Since 1848, at the same time as studying at the seminary, he was attending classes at the Imperial Academy of Arts. In 1850, he was awarded the title of an artist from the Academy, and in 1854, he was awarded the title of academician for the portrait of the rector of St. Petersburg Theological Academy, Right Reverend Makarii (1853). In the spring of 1855, he took a position as a teacher of painting and icon painting at St. Petersburg Theological Seminary.

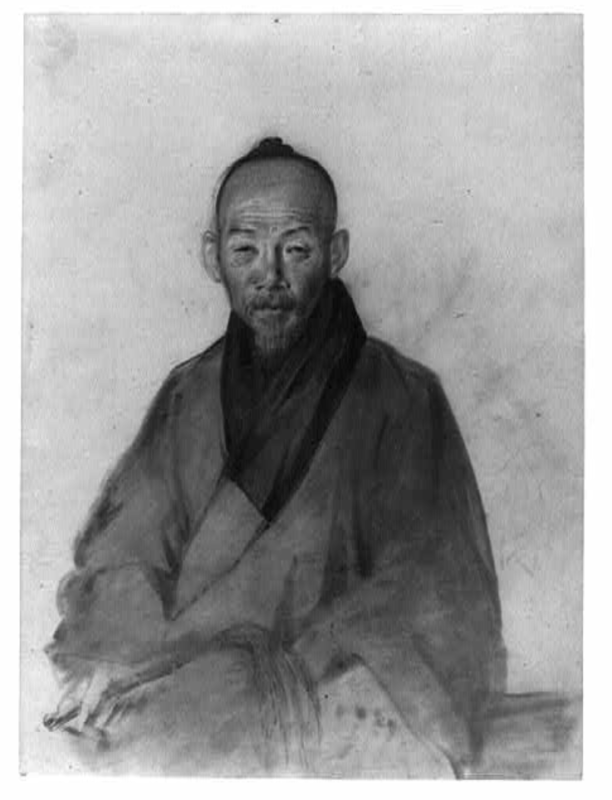

In January 1857, according to his expressed desire, he joined the staff of the Beijing Ecclesiastical Mission as an artist. On the way to China, he stopped in Irkutsk and Kyakhta. He left Beijing with the mission in 1863 and arrived in St. Petersburg in February 1864. After completing the trip, the artist exhibited eight paintings at the Academy of Arts in 1865, including the work "Chinese beggars in the cold," which is now kept in the Tretyakov Gallery. In addition to this canvas, images of "various Chinese types" were exhibited: "officials in junior rank," "officials in summer dress," "the head of the department of Foreign Affairs," "soldier of the yellow banner, Christian, 75 years old," "tatar," "merchant, born Mandzhur," "doctor, born Chinese," etc. It is established that the album with ethnographic views of China was presented to the Crown Prince (probably, we are talking about Nicholay, the eldest son of Alexander II); the artist was presented with a diamond pin in gratitude. The further fate of the St. Petersburg album with views of China is currently unknown to researchers.

In addition to the painting "Chinese beggars in the cold" and one portrait dated 1860, the location of other works by Igorev, made by him in China, is unknown at the moment, according to experts in the history of painting and local historians of Saratov.

The artist left "Memoirs of the academician of the Academy of Arts of L. S. Igorev." Lev Stepanovich definitely visited many places in China, which are precisely identified by the images. We are talking about some sections of the Great Wall of China, the vicinity of Beijing, Buddhist temples. In 1862, the article "The trip of the Russian artist to the surrounding mountains of Beijing" was published by the Trans-Baikal newspaper "Kyakhtinskiy listok." The study of the article makes it obvious that many of the themes of the images, the ethnographic subjects of the "Russian Album" directly correspond to the artist’s travel impressions. He wrote that he was shocked by Chinese beggars, "God! What beggars are these here! My heart stops when I look at them." It surprised him that he met few women on the streets, as in China it was considered unworthy for women to go around on foot. The artist found the tradition of bandaging and disfiguring the legs to make them seem small strange. He was shocked by the whitewashed faces of Chinese women, which seemed "completely plaster" [Igorev 1862 p. 5, 11]. All Europeans turned out to be shocked by similar features of Chinese life.

The convincing art history arguments will be given as well. Consultations with the honored artist of the Russian Federation, the corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Arts, the professor, the head of the department of graphics, the head of the creative workshop of easel graphics of painting of Krasnoyarsk Art Institute V. P. Teplov, who studied the views from the "Russian Album," allow us to conclude that the drawings belong to several authors. Some of the works (portrait of an Asian, portrait of a Chinese, a scientist, a portrait of an official or a gentleman, a portrait of a young scientist) can be evaluated as the work of a professional who worked in a realistic Russian manner, removing unnecessary details, smoothing the shape, creating a good background. The hand of a master who received an artistic European education is visible. In addition, between the drawing "Portrait of an Asian" and the accurately attributed painting "Chinese beggars in the cold," which is currently presented in the Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow), there are many similarities concerning the features of Chinese faces, the image of their hands. There is every reason to believe that the American part of the Yudin collection contains the works of L. S. Igorev.

Some of the drawings, which are very convincing, were painted by Chinese artists. This is indicated by the specific composition of the images, the authors’ tendency to generalize, their commitment to expanded frontal images, and the specific ethnographic nature of the drawing. Finally, the presence of complex hieroglyphs to the right and left of the image suggests that the album featured the work of Chinese artists. The most important feature of the Chinese visual tradition, the inseparable unity of painting, drawing, and calligraphy is reflected in the drawings of the album. Artists used brushes and ink to paint pictures on paper.

Moreover, as established by Russian researchers, paintings of an ethnographic nature were often ordered by the Chinese. In the correspondence of L. S. Igorev with the priest of Irkutsk church, there are numerous references to acquaintance and cooperation with Chinese painters, as well as Catholic artists (these could be only one person). Igorev could not draw a view of the Temple of the Immaculate Conception (Eastern temple) personally, as it laid under ruins during his residence in Beijing. In a letter of 1860, he told a reporter in Irkutsk that among four Catholic temples in Beijing, "The Southern temple remained the same, although it left for several years with a gilded brick entrance… The Eastern one does not exist at all, but there is only one rafter surrounding it that belongs to it. The Northern temple has only one foundation and the surrounding buildings. The Western temple is known for the place it used to be" [Larchenko 2016 p. 17]. Finally, L. S. Igor, as it was found out from his memories published in the last year of his life, knew only spoken Chinese, "...I studied the language, not literary, but everyday language, without which it was impossible to live. I learned to talk" [Igorev 1893 p. 371]. He could not write any texts in Chinese.

Painting some images suggested familiarity with the topographical features. We are talking about plans and so-called "bird’s-eye views." Images of cities and estates plans could be made by a person, who, most likely, had a special topographical education. It could probably be Ya. G. Shimkovich. In 1859–1861, the military topographer Shimkovich, in the embassy of Major General N. P. Ignatiev in China, made route surveys from Kyakhta to Beijing and from Beijing to Bey-Tan. He also made accurate plans of the cities of Beijing and Tut-Uzhou with the surrounding area. For the difference shown in this case, he was promoted to a warrant officer [Sergeev 2001, p. 341].

As for Dr. P. A. Kornievsky, the authors of this publication have accurate information that his handwritten legacy does not include 29 Chinese drawings made for General Ignatiev in 1860 (as stated in the Allen Memorandum), but "a description of Chinese drawings (made for General Ignatiev in 1860 (291 p.) [Handwritten legacy...] in the Beijing doctor’s diary, which consists of 587 pages of typewritten text, first discovered in 1965 and partially published, there is no information about the doctor’s artistic activities or the creation of sketches of an ethnographic nature" [Efimov, p. 141–142].

Images from the "Russian" (Chinese) album still exist today. A number of foreign companies offer consumers reproductions-posters with Chinese species from the Yudin collection for a moderate fee ($10-15). This information is freely available on the Internet [Photo]. The history of the origin and existence of the images is not specified. Drawings from the Yudin album are used to illustrate works on the history of the Christianization of China.

Thus, the American part of the collection of G. Yudin contains valuable artistic and ethnographic material on the history of Eurasia of the XIX century. The "Russian Album of China" reflects the traditional features of Chinese life fully and the first modernist processes in society. The images give an idea of the disappeared or reconstructed art objects of China. The study of cultural contacts between Russia and China in the XIX century found vivid expression in the work of Russian artists, in the visual discovery of everyday life in China. It is established that Russian and Chinese artists participated in the creation of drawings and sketches collected in the album. The circumstances of the creation of the series of images indicate the established artistic contacts between Russians and representatives of the Chinese community by the middle of the XIX century.

The album is worth keeping on studying. The attribution work has to be completed. We consider it reasonable to combine the efforts of scientists from Siberia and the Far East in cooperation with their Chinese colleagues to study the theme of visualizing the life of China in Russian artists' works, as well as to hold an international conference devoted to this subject matter.

References

The eighth Yudin Readings: conference proceedings. (Krasnoyarsk, October 13–16, 2015: in two parts. – Krasnoyarsk: State Unitary Enterprise, 2015. –240 + 292 p.

Efimov G. V. Peking diary of the doctor of the Russian spiritual mission P.A. Kornievsky / / The peoples of Asia and Africa. – 1965. – № 6. – pp. 141–142.

Igorev L. S. Memories of academician AH L. S. Igorev // Saratov region. Saratov, 1893. – Issue. 1. – pp. 363–372.

Igorev L. S. A trip of a Russian artist to the neighboring mountains of Beijing // Kyakhtinsky leaflet. 1862. – № 18. – pp. 5–12.

Laih H. Correspondence of the Director of the Library of Congress with the US President: to the history of the acquisition of the library // Library Science. – 2013. – № 4. – pp. 82–86.

Larchenko V.Yu. Catholic missionary work in China through the eyes of Lev Stepanovich Igorev // Advances in modern science and education. 2016. – № 8. – pp. 16–19.

Nesterova E.V. the Russian Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission in Beijing and the beginning of Russian-Chinese contacts in the field of fine arts (new archival materials) // Orthodoxy in the Far East. 275th anniversary of the Russian spiritual mission in China. – St. Petersburg: Andreev and Sons, 1993. – pp. 127–133.

Polovnikova I. V. Gennady Vasilyevich Yudin. A life. Library. – Moscow: Publishing House «News», 2010. – 456 p.

Manuscript heritage of Russian Sinologists URL // http://www.vostlit.info/Texts/Dokumenty/China/Rukopis_nasled/text.htm (Date of circulation 1.04. 2018)

Samoylov N. A. China in the works of Russian artists of the XVIII–XIX centuries // Bulletin of RFBR. Humanities and Social sciences. 2016. – No. 1 (82). – pp. 25–41.

Sergeyev S.V., Dolgov E. I. Military topographers of the Russian army. M.: ZAO SiDiPress, 2001. – 592 p.

Yudin meeting of Krasnoyarsk Regional Scientific Library: catalog. Issue. 13. Geography. – Krasnoyarsk, 2004. –118 p.

Yudin meeting of Krasnoyarsk Regional Scientific Library: catalog. Issue. 14. History. – Krasnoyarsk, 2006. – 215 p.

Meeting of Frontiers: The Gennadii V. Yudin Collection of Russian-American Company Papers // URL // https: //memory.loc.gov/intldl/mfdicol/mtfyumTitles1.html#top (Date of circulation 01.30.2018)

The New Encyclopedia Britannica. 15 ed. – V. 26. – Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2005. – p. 983

Russian drawings of China URL // https: //www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b32419/ (Date of circulation 26.02.2018–1.04.2018)

Photo: Ladies’ hair styles, heads of 20 Chinese women, 1860–1910 URL // https: //www.amazon.com/Photo-Ladies-Chinese-1860-1910 (Date of circulation 10.03.2018)