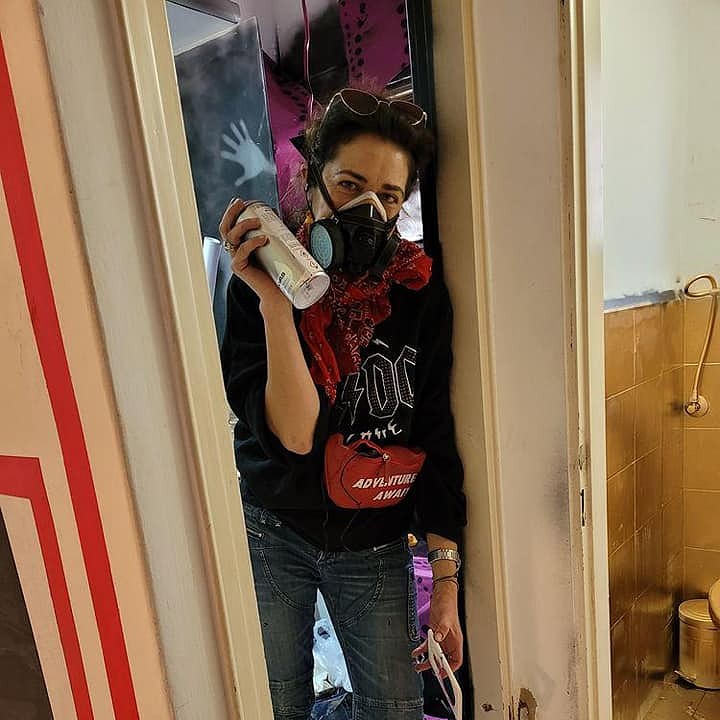

Julia Shtengelov, aka Imaginary Duck, is an Israeli street artist. Her signature girl figures in black, red, and white can be seen in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and other cities around the country. Her mixed media works combine painting with plaster casts that make the inanimate characters almost living beings. Fine Art Shippers spoke with Julia Shtengelov about the origins of her art and her passion for technology.

Artist Talk: Imaginary Duck Julia Shtengelov

You work in IT and you are also an artist. How did art come into your life? When did you start as a street artist?

Julia Shtengelov: It happened spontaneously, I did not plan it. It was 2009, a strange time in my life; everything was falling apart. I was looking for something different from what I had, a kind of escape. I needed to get out of my comfort zone but could not afford common ways like traveling or studying, so I was looking for an alternative solution. With the methodology of the theory of constraints of Eliyahu Goldratt, the answer came naturally: street art. I wanted to do something creative to keep my hands busy and my head clear while bringing adrenaline and a spirit of adventure into my life. And I also felt the need to make other people smile. I concluded that street art met all those criteria. So I went out on the street and made my first piece of art. At the time, I could not imagine it would last long, maybe a year or two. But I've been doing it for thirteen years already.

Do you have any artistic training? Was art present in your life when you were growing up?

Art has always been there. We had a lot of art albums and books at home. My older sister attended an art school, and since I always looked up to her, I also enrolled in a children's art school, where I studied for only two years. This was in Smolensk, Russia before our family moved to Israel. Although I did not continue my art education in Tel Aviv, from time to time I drew and doodled in my notebook. But overall, I was more interested in technology, so I chose to study at Beer-Sheva Technological College. I was always dedicated to my career in my own way and never regretted choosing this profession. In this respect, I took after my father, who was a systems analyst and had a passion for technology, he inspired my interest in math and innovations. The computer was the first piece of equipment we bought in Israel in 1990.

There are recurring characters in your art – a duck and a girl. What meaning do they have for you? How did they come about?

The cute, fluffy duck has been my favorite motif since childhood. I love these birds, somehow they are always present in my surroundings. When I started doing street art, I was looking for something special, quick to apply, funny, and recognizable. One day I walked into an art store and came across plaster molds for casting. There were hearts, angels, tractors, flowers, and ducks. So I bought three duck molds and started casting at home. I would paint those casts and tape them to the walls when I went outside. That's how my pseudonym Imaginary Duck came about.

As for the girl, it also goes back to a mold I bought at a craft store in the early 2000s. Back then, I didn't know why I needed it but I felt that one day I would. And eventually, the time came. I found that the face offered more room for creativity: you could paint different expressions on her face or dress her differently. I cast these faces, pasted them on the walls, and painted the body in acrylic.

Street art is often socially and politically engaged. Do your works also have political messages?

At first, I tried not to address political issues. But there are things you just can't ignore. In 2019, we had protests against the increased cost of living. That inspired me to do a series of works showing Marie Antoinette with a cigar and a wine glass in her hands. The inscription on the paintings read, "Let them eat the cakes." The phrase is commonly attributed to Marie Antoinette. There are references to it prior to the French Revolution, which means that the quotation cannot possibly have come from Antoinette, but I have attributed these words in allusion to the wealthy establishment.

Other works from the same period were inspired by the new Covid reality. Two of them were included in an album published in France in 2021, featuring more than 250 street artists from around the world. And my more recent series depicts girls wearing pig masks and a quote from Orwell, "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others."

Do you get commissions for your art?

Yes, periodically, people reach out to me, saying they like my art and would like to have it in their homes. I paint on almost everything: wood panels, canvases, paper, metal, etc. I like experimenting with different mediums. I have a lot of my art at home and once or twice a year I do a kind of party-exhibition where anyone can come and buy what they like.

How is street art treated in Israel? What's the general attitude?

I would say the Pareto principle (80% of consequences result from 20% of causes) applies to street art as well. I mean, the attitude is mostly positive, but there is still some negativity. I am talking about ordinary people here, not the police. Some people adore it, some hate it, and some ignore it.

Photo courtesy by Julia Shtengelov