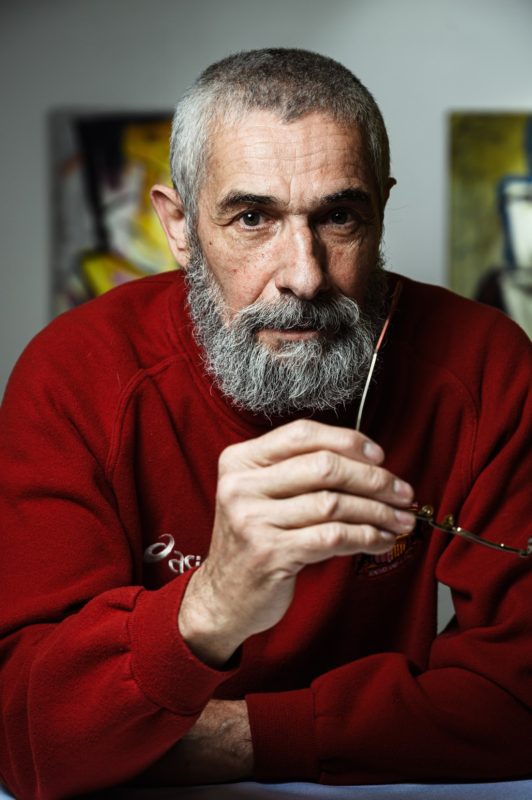

On May 18, a solo exhibition-retrospective of works by the Moscow artist Roman Aivazian opened in the halls of the Tapan Museum in Moscow. Roman has been making art all his life and has come a long way in finding his unique style. His works are in private collections around the world, and his main exhibition activity in recent years has been concentrated in Europe. We talked to Roman about his creative method, his main sources of inspiration, and life in general.

Interviewer: Your paintings are very expressive; they often contain the nerve of pain, the emotion of suffering. Is it a property of your character or a response to the imperfection of the world?

I would say in the words of ancestors and great thinkers, “who increases knowledge, increases grief.” After all, what surrounds us? Yes, nature is beautiful, it is wonderful, it is magnificent. But everything else that people do... Wars… Children suffer, women suffer. How can an artist pass by this and not reflect it in their canvases? For me, for example, it is impossible to pass by, I must definitely process these feelings and reflect them in my art because it torments me, it worries me because I suffer together with all of them. There is nothing good in any negative.

I would also add that there is some irony and, perhaps, even mockery in my work. This is the style of my life, and this style was not chosen by me, it was chosen by time, fate, maybe. Sorrow – it pursues, it is near, as well as the pain and more sorrow. But beauty and, of course, everything beautiful that surrounds you are also nearby. And the artist absorbs everything.

And if they set themselves the global task of fulfilling their duty – to reflect this in their works, then they will certainly achieve the goal, no matter what it costs them, no matter how difficult it is.

Because it’s hard for them if they can’t reflect this; in fact, it’s very hard. All of this accumulates and then spills out into canvases, into paintings. In different ways, of course: sometimes energetically, sometimes with some apathy, depending on what you paint.

Interviewer: The wide color palette and the brightness of the colors in your work evoke a feeling of inseparable connection with the impressions of a childhood spent among the vibrant nature of Georgia, while you rarely use natural objects in their realistic form. Does this mean that you create the form, composition, and color within yourself?

Interviewer: The wide color palette and the brightness of the colors in your work evoke a feeling of inseparable connection with the impressions of a childhood spent among the vibrant nature of Georgia, while you rarely use natural objects in their realistic form. Does this mean that you create the form, composition, and color within yourself?

Yes. I create the form, color, and composition within myself. In no case should an artist forget about the form because painting itself can become so expressive that the color of the paints may not even be enough, but at some point, you realize that you must return to where you started so that the idea, the energy could take shape and become whole on the canvas. It is important for me to convey my vision to the viewer in the very form with which the viewer can interact, which they can perceive. And I am grateful to my teachers for not letting me break my individual view of creativity, but at the same time, they taught me a lot in terms of technology. Technique still remains an integral component of painting, no less important than the idea and content themselves.

Interviewer: Do you have idols and teachers among the outstanding artists of the past, or, on the contrary, do you try to avoid anyone's influence, although this is not easy?

It was not easy in youth because in youth and in childhood, I would say, most likely, in childhood, this is the very time when the spirit is formed. All those qualities formed, you would later carry throughout your life, short or long, it doesn’t matter – you collect them and carry them inside yourself, save and consolidate. You carry them throughout your life and artistic path. A teacher is needed at that time. And I had a good teacher. It was the wonderful Tbilisi artist Irina Grigorievna Fedosova who taught me painting. I also did the wood carving, and I had a very good teacher in Kakheti for that, Felix Azimovich Azamatov. I went to see him every day for a year when I was fifteen years old. He, probably, told me everything he knew. He was a famous sculptor and wood carver.

He taught me from the very beginning: how to hold a chisel correctly, how to hold a knife correctly. As for the choice of wood, in Georgia, there was an abundance of it: mahogany, sycamore, boxwood – beautiful, magnificent materials. I made both small forms and large sculptures. Already in Moscow, I switched to bronze. All this helped in my work, in painting. For the past few years, I have not been making sculptures because I have other tasks, other goals – I want to paint more canvases, devote more time to painting because my main goal since childhood has been achieving perfection in painting.

I'm obsessed, of course, with this idea. This word is forgotten, but I remind you that there is such a thing as obsession. Obsession is exactly the very goal you are going toward, which you have set for yourself. This is the miracle that you have discovered in yourself. This is what you're going for. I've been going to this for many years, and only at the age of 40, I finally realized that there is such a thing in me. And in no case should this opportunity be missed. Because there are so many beautiful things, so many marvelous things, absolutely everything around. I consider myself a happy person because I am moving toward my goal, and I thank the Creator for what He gives me every day. And I ask the Lord for the next day because I know that the next day will be different, it will bring new fruits. It will bring what I have not come to today yet. And as for the idols, I have never had them.

Interviewer: Do you divide your creativity into periods, or is there a search and experiment in each time frame, a desire not to stop at any specific style?

This is a very good question. You need to work hard; you need to work very hard; and you need to paint for many hours every day.

It's hard work if you paint and think. And if you simply copy or engage in, let’s say, imitation of the works by Barbizon or Impressionist artists, then you will not create anything new.

In addition to beauty, there is another form, one object that is probably also forgotten. It's a charm. Charm has been studied but not comprehended in contrast to beauty, which has been much studied and comprehended by all people of all times. Charm has not. Charm is another thing. It's like a fire, a flame. The flame is the greatest, the most ingenious creation of the Almighty, capable of taking on the most bizarre forms, new forms. It's all visible, no need to invent anything. In general, there is nothing to take from nature because everything has already been taken by Barbizon artists, Impressionists, and the Wanderers.

And I would like to discover something new for myself, yes, something new, my goal is just that.

I want to find my style and unique manner, to create something new. It is difficult in painting because painting is an ancient craft and to find something new, to create something, you need to enter such Nirvana that I can’t even imagine myself yet. But I am moving toward this goal, and I feel that I have everything to achieve it.

As for the periods, I would not divide my work into periods. Why? Because, frankly, I'm not very interested in it. I don't want to repeat myself, I don't want to imitate anyone, and I don't want to divide my work into periods. I would say in another way: for me, steps are a more appropriate concept and sculptural form. Pass one step, then pass the next step, rise higher, go on without stopping, as I said. Every day, I have one step because every day, I learn something new, and I set myself the goal of going further, stepping up the stairs that I created myself to my airship. Without stopping no matter what, without looking back until the lions become lambs.

Interviewer: Please tell us in more detail why you decided not to make sculptures anymore. Maybe because there is no color in it, which is your main artistic means of self-expression?

Let's start with what Michelangelo once said, “sculpture and painting are different things.” And sculpture, perhaps, is at a higher level. That is because, firstly, it is hard physical labor, and secondly, it is more difficult and harder to express oneself in sculpture than in painting. I have been sculpting since I was 14 years old, but I chose painting because I have always liked color. It is in the blood apparently because I was born in sunny Georgia. As for sculpture, I have always liked wood sculpture – it is warm, every tree is an organism. Before you start doing something, as the great ones said, you first whisper to this piece of stone or wood and then start working. Wooden sculpture gave me a lot, really a lot. I would say that if it weren't for wood, maybe I wouldn't set such complex and lofty goals for myself in painting now. From sculpture, I took for myself everything that I specifically needed, and I always carved with great pleasure. Now I use and will use this experience because I have always loved sculpture, I have always liked it, but I like painting more because painting is color, it is paint, it is fire, you can’t achieve this in sculpture.

Interviewer: You were a member of the Union of Artists of the USSR. Why did you leave the union in the 90s? Do you think creative unions are useless ballast?

The Union of Artists in Georgia gave me a lot; I worked fruitfully there, largely thanks to Zurab Tsereteli. With gratitude, I want to convey to him big fiery Caucasian greetings. He is a worthy man. I perceive everything, including people, through myself. He personally gave me a job because I came to him. It was 1986. I explained everything to him, but he didn’t even listen to the end and gave me a job. I earned money and returned to Moscow.

And I said goodbye to the Union of Artists in Moscow in 1995. It was simply not very interesting for me to be a member of it at the time. I sent a lot of my artist friends abroad then, some to America, some to Germany. Many left. I can remember a lot and name a whole bunch of names. But I don’t want to live in the past. I want to live in the present, and I want to live in tomorrow. And what happened in the past, I, frankly speaking, do not want to remember. I believe that living in the past is a weakness. We must live for today, at least, today.

Interviewer: Roman, thank you very much for the interesting dialogue. We remind our readers that the solo exhibition-retrospective of the artist Roman Aivazian is open at the Tapan Museum in Moscow until June 18. The exhibition presents paintings and graphic works created from 1990 to 2023, which allows you to fully trace the path of the artist.