New York-based artist Artem Mirolevich creates whimsical, extremely detailed works full of mythical references. His surrealistic imagery draws you into a dystopian but at the same time very attractive world.

Fine Art Shippers spoke with Artem Mirolevich about his artistic influences, career journey, and some of his most important projects.

Artist Talk: Artem Mirolevich and His Optimistic Postapocalypse

You are now an established artist with regular solo and group shows and an impressive portfolio. How did your professional journey start? Did you always want to be an artist?

Artem Mirolevich: I was born in 1976 in Minsk in the then Soviet Union and came to America with my parents when I was 17. At that time, I already knew that I wanted to become an artist, although six months earlier I'd had no idea what to do with my life. We settled in Buffalo. It's a small town with no art scene, but I was lucky to meet a fantastic teacher, Bunny Leighton. She is elderly now and we still keep in touch, I call her regularly. She saw a talent in me and taught me a lot about artistic vision and techniques. I remember her telling me that I needed to go to college in New York City or Los Angeles if I wanted to pursue a career in the arts. She promised to do everything she could to help me, and she did.

On her advice, I applied to one of the best art schools in America – the School of Visual Art in New York City. When I showed up there for an interview, another stroke of luck was waiting for me. I showed the professor my work. After looking at them for a while with obvious interest, she left the room and came back to tell me that the school still had a full scholarship left and that they'd give it to me.

What kind of training did you receive at the School of Visual Art?

American art schools generally offer less academic training than European ones, they focus a lot on nurturing your artistic vision. There's a lot of freedom in what you can do. At the same time, I felt I lacked some academic skills. So when I applied for an internship, I chose the Rietveld Art Academy in Amsterdam. Why not Italy or France, for example? My reasoning was: if New York is New Amsterdam, I should go to the Netherlands to explore the origins of my new country. I spent an entire semester in Amsterdam. It was probably the best time in all four years of my studies because I didn't have to earn a living like I did in New York, but could devote myself entirely to my studies. I also met one of my best friends there, Frederik Knothe, who's now one of the chief designers at Mercedes. We shared a house in Amsterdam.

Your work has an air of mysticism and is full of mythical references. What is this world that appears in your works?

My work was inspired mainly by literature. I've been an avid reader since childhood. Thanks to my rich imagination, I was able to depict everything I read very vividly. Music is also a great source of inspiration for me. One of the musicians who strongly influenced my worldview is Boris Grebenshchikov. I loved the metaphoric nature and philosophy of his songs. I think intuitively I've always been attracted to the works of art that fed my imagination.

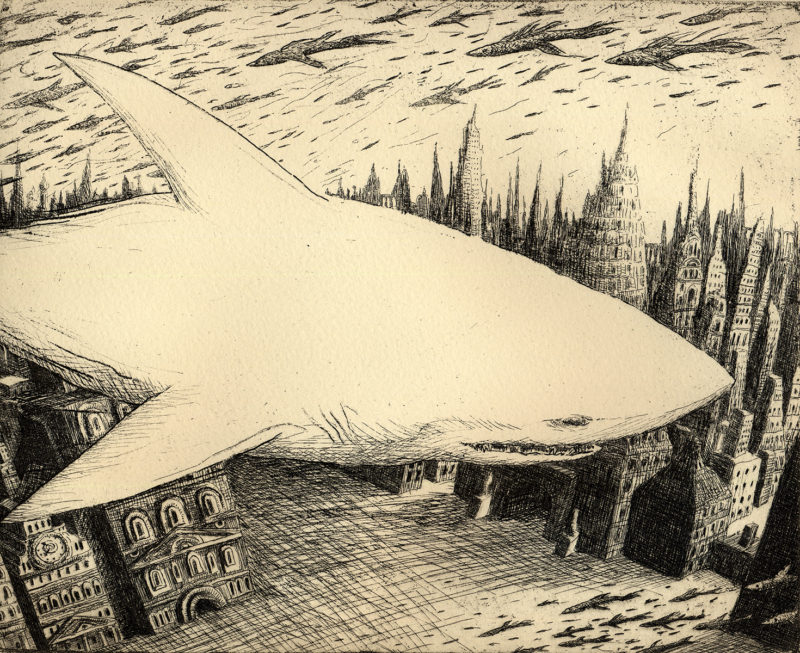

My art is the projection of my inner world, which sometimes explodes with ideas. One of them is the concept of the mothership that carries under its keel the remains of our civilization. I jokingly call this image an optimistic postapocalypse. It's a kind of mixture of Noah's Ark, the Tower of Babel, and the Flying Dutchman. This ship can be a symbol of rebirth or another round of the fateful spiral. It's sort of a warning to humanity about the deteriorating environment and the civilizational changes that are now taking place.

Is that the message you would like to get across through your art?

As an artist, I'm just a transmitter, not even conveying messages, but fleeting ideas that are out there but haven't yet been articulated. I often notice how an idea is born in a split second as if someone just put it in my head. Sometimes, though, it's a long process in which the idea gradually evolves. I feel like it's leading me in a certain direction, and I just follow where it goes. I can start a painting knowing exactly what I want to do, but at some point, it takes on a life of its own that I've no control over.

You make oil paintings, prints, and collages. Which medium do you love most?

I'm first and foremost a graphic artist, I think graphically. That doesn't mean I translate my ideas exclusively into black and white, but I'm primarily interested in the idea, and only then do I think about the color, light, etc. But I also love oil painting. Most of the time, I alternate periods of graphic and oil work. This also has to do with my artistic routine. Graphic works are smaller and therefore require less time to execute. Yet they're full of small details. Oil paintings take longer, are no less detailed, and are more about creating a bigger picture and perspective. I love going from the micro level to the macro level. However, both often overlap in all my work, regardless of format.

You received training as an illustrator at the art school. When and why did you decide to pursue your career as an independent artist?

After art school, I worked as an illustrator for a while. I did a lot of covers for books, magazines, and music albums. I still do that sometimes. But I always felt that illustrating other people's ideas wasn't enough for me. I wanted to convey my own thoughts and ideas through art. And I was lucky – shortly after I graduated, my friends helped me organize a solo exhibition, which was quite a success, with half of the works sold out. That gave me the confidence to continue on my own path. There have been some ups and downs, for example, my contract with a renowned gallery in Chelsea, which I was very proud of in the beginning, turned out to be a financial failure. Since then, I've become very cautious. But I've met and worked with fantastic galleries and art dealers. So overall my experience has been positive, I can't complain.

You were the founder and curator of the Russian Pavilion in New York City. Can you tell us more about this project?

In the early 2000s, Russian contemporary art was booming, and Russian artists were increasingly represented at major events such as international art fairs and biennials.

In 2012, a friend called me and suggested doing a joint exhibition. But I wanted to go further and organize a major show of Russian artists in New York. For that, I needed the support of an established artist. And I turned to one of the most famous and respected Russian artists in America, Ernst Neizvestny. He was a real colossus whom I admire. He agreed to support our project and provide several works. That's how I was able to attract sponsors and raise the money necessary for such an ambitious enterprise. By 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, we'd held ten successful exhibitions. By 2015, I realized that the Russian Pavilion was no longer relevant, as the concept of the "Russian world" brought a lot of controversy.

What has the experience of realizing large-scale projects given you professionally?

I personally curated all the exhibitions of the Russian Pavilion, and all of them were part of major events like Art Basel Miami. It's been a fantastic experience. I've learned a lot about fundraising. Before, I could hardly imagine calling a stranger to ask for sponsorship. But when you ask for money for a specific project with clear goals, it's much easier.

I've since opened a gallery where I represent artists on a commercial basis. Just recently, we participated in Armory Arts Week, New York, and Art Basel Miami, where I put together an exhibition of thirty-five artists. So curating has become an important part of my life as an artist.

Follow Artem Mirolevich on Instagram - @arte_miro. Photo courtesy of Artem Mirolevich