Graham Shay 1857 is a private art gallery specializing in fine American paintings and American and European sculpture, with works ranging from the 1840s through the 20th century. It is located in a private apartment building steps from Madison Avenue and carries on the legacy of one of the oldest galleries in America.

Fine Art Shippers spoke with its director Cameron M. Shay, one of the most regarded experts in 19th and 20th-century American and European sculpture, about the gallery’s history, recent exhibitions, and the most gratifying part of art dealing.

Graham Shay 1857

What initially drew you to the art field?

Cameron Shay: I had no formal art education, but my grandparents were collectors. I grew up visiting them in their home. I think that’s where it began—sort of organically absorbing that. My parents were collectors as well. I remember uncrating paintings and sculptures with my father and spending hours reading the catalogs and art books they had. I just loved it. I think that was my education, through my grandparents and parents, and that’s what led me to the art field.

Why did you choose to focus on 19th and 20th-century art, specifically American and European sculpture and painting?

My father was a Western art collector—both historic and contemporary Western paintings. Not surprisingly, my first job after college was in a Western art gallery as well. For four years, I worked as an art dealer in Wyoming, Arizona, and Texas. But I always wanted to live in New York, so I interviewed at various companies and auction houses in NYC and was lucky to take a job with the firm I’m still with today. It’s the oldest family-run gallery in the city and one of the oldest in America—James Graham & Sons, established in 1857, still in the same family five generations later.

This is an exciting story. How has your career with this gallery developed over the years?

My mentor there, Mr. James Graham, taught me so much. He is an expert in sculpture and taught me almost everything I know about it. It became one of my specialties, particularly American sculpture. Working with him, I gradually transitioned from Western art to the broader field of American and European art.

I’ve been a partner in the firm since the 1990s, and in 2018, I added my name to the gallery. It used to be known as the Graham Gallery, or James Graham & Sons, and now it’s called Graham Shay 1857. I’ve kept the year in the name to honor the gallery’s founding.

Your gallery regularly organizes exhibitions. What recent shows stand out for you personally?

We've had two successful shows most recently, both were large exhibitions sourced from many different places, collections, and institutions. One that took place in the fall of last year was dedicated to the artists of the celebrated 1913 Armory Exhibition. We managed to put together 70 works by artists who exhibited in the 1913 show.

The second show this spring was celebrating the 135th anniversary of the National Association of Women Artists, the oldest women artists' collective in the United States, which provides a community for professional women artists. It involved a lot of time and effort to gather all the works as well, but I’m very happy with the result.

Could you tell us a little about the current exhibition of Francisco Zúñiga?

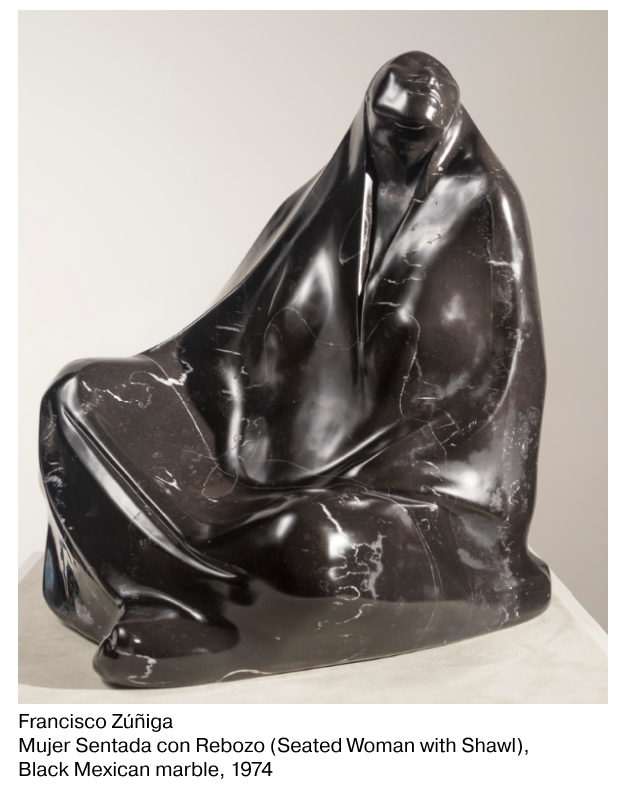

Although originally from South America, Zúñiga is considered a Mexican artist as his life and career were in Mexico. This is a very small exhibition showcasing two of his favorite mediums, bronze and marble. For some time, I have owned a magnificent black Mexican marble sculpture of one of his classic figures—a seated Mexican peasant woman draped in a robe. It's a beautiful piece, featured in the catalog raisonné. Recently, I acquired an extraordinary bronze from 1974, and that gave me the idea to create a small exhibition of these works, representing his two main mediums. The bronze figure, “Bending Woman,” was part of an important exhibition curated by the San Diego Fine Art Museum and later featured at the Phoenix Art Museum.

An interesting detail that I find personally touching is the resemblance to Alexander Stirling Calder's 1920 masterpiece at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Girl Scratching Her Heel,” which has always been one of my favorite sculptures. Zúñiga must have seen this and been inspired by it.

You have helped build many institutional and private art collections in America. What do you find the most gratifying part of your job?

I've had the privilege of working with many leading institutions in America, as well as private collectors, some of whom I've been advising for over 30 years, helping them build their collections piece by piece. It's incredibly satisfying to have such a long-standing relationship with clients.

Many of them, like great collectors in general, are incredibly knowledgeable and passionate about art. They do a tremendous amount of research, though they might not have the same connections as I do. They rely on me and other specialists to bring them works that would become gems in their collections. This is the best part of my job.

I’m curious about some memorable discoveries you've made in the course of your career. Could you share a few that particularly impressed you?

There’ve been so many. I've been blessed to have been doing this for a long time, and I've had many discoveries over the years. But one story stands out, and it’s one I tell sometimes.

I have expertise in the sculpture of Frederic Remington, and I’m listed on the Frederic Remington Art Museum website. Since they don’t want to be involved with authenticating his sculptures, they refer people to a handful of experts, including me. Remington’s sculptures were so popular that there are many fakes, reproductions, museum castings, and recasts—thousands of them out there. I get called weekly or even daily to authenticate Remington bronzes. I'd say 99.9% of the time, they turn out to be reproductions. But over 35 years, I’ve found some authentic ones, which is why I always take every call.

One day I got a call from a Dallas public school administrator to authenticate a bronze. She had bought it as a reproduction of a Remington at a small auction and enjoyed it for many years at home. A friend suggested she check if it was real, just in case. So she found me and sent me some photos, and when I saw them, my heart skipped a beat. As I went through the process, every step further convinced me that the piece was authentic. In the end, it was.

We agreed that I would sell the piece for her. That sale allowed her to buy a retirement home in Santa Fe, New Mexico—something she wouldn’t have been able to do without that discovery. That same year, I happened to be traveling to Santa Fe on business, so I visited her and her family in their new home. It was a wonderful ending to that wonderful story.

Interview by Inna Logunova

Photo courtesy of Graham Shay 1857