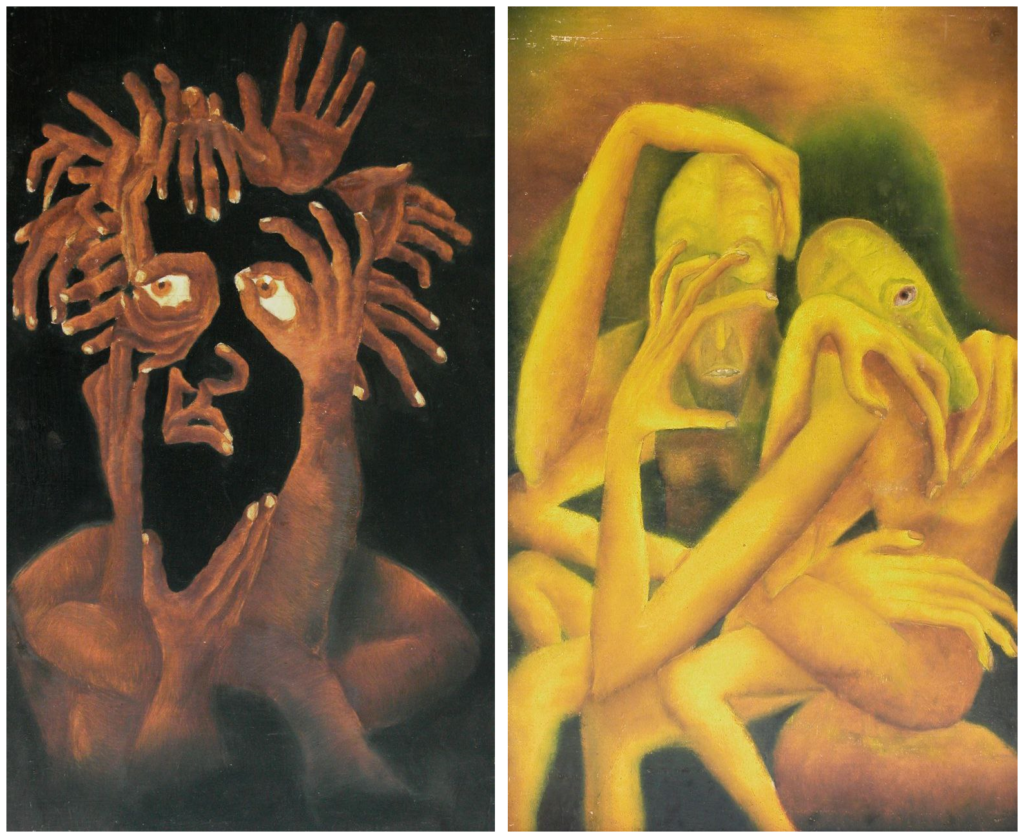

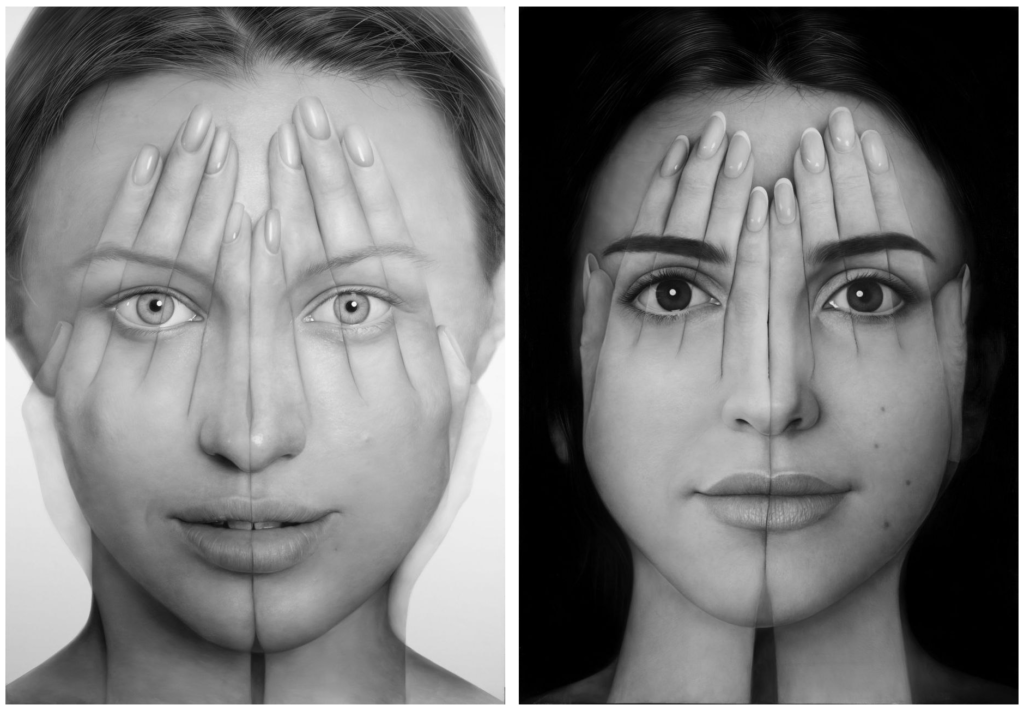

His immediately recognizable paintings explore the pain points of contemporary society through subtle metaphors and expressive visual language. While Fine Art Shippers previously spoke with Tigran about his current projects, this time we decided to explore his beginnings and how his early childhood experiences shaped him as an artist.

I’m curious about your early life and your family—what were your parents like, and what were their interests and occupations?

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan: My mom is a pianist. She’s spent her whole life with the piano, practicing seven hours a day. I literally grew up under it—I know every piano piece by heart. My dad was an engineer, but he was a true jack-of-all-trades. He could do anything and was interested in all kinds of things, and maybe that’s why he never stuck to one thing. He invented a car tape recorder when he was young, and even had a factory for it, but when Sony bought the rights, he quit and moved on to photography. That’s how he met my mom—doing her screen tests for a film. She was very beautiful and had offers from one of the Soviet Union’s major studios, Mosfilm, but when my dad asked her to choose between him and the movies, she chose him. She stuck with music but still played in a few films.

After photography, my dad got into researching Armenian folk music. He traveled all over Armenia, recording old songs from elderly people. Our house was filled with these recordings. He also made wood sculptures. He even built our whole country house himself. That was him—curious, talented, always onto something new.

What was it like growing up in such a creative atmosphere? Did it feel natural to you, or was it more like a magical world you wanted to be part of?

It felt completely natural. Beyond the creative vibe, our home was kind of an anti-Soviet headquarters. Our home was always filled with Armenia’s intellectuals, talking until morning. My dad had a massive library of world philosophy—books that were banned at the time. Those were hand-copied texts—because you couldn’t buy them anywhere then—hidden behind fake covers.

We also had around four thousand vinyl records—mostly jazz and classical music. Music played round the clock at our place, and always with incredible sound quality. We probably had the best audio equipment in the entire Soviet Union. My dad even sold his car to buy a specific amplifier. We didn’t even have proper furniture because he spent all his money on vinyl. At first, we literally had stones instead of chairs. Eventually, we got some furniture, but everything stayed very minimal. But the atmosphere was incredible.

From your memories, what was Yerevan like back then—visually and culturally? What kind of impression did the city make on you?

It’s hard to compare because I was just a kid, but everyone said Yerevan was one of the freest cities in the Soviet Union. There was a sense of openness—you could feel it in the atmosphere. Yerevan was the only Soviet city with open-air cafes, where people could just sit and talk. It was a very creative place, full of artistic energy. Back then, material values didn’t mean much. Conversations were about ideas, philosophy, and culture, and that set the tone for everything.

Your artistic career started very early—you had solo shows already as a teenager. Could you talk more about that?

I started painting when I was five. I was painting an oil painting a day, and we had a “drying wall” at home where all my wet paintings hung. It became a bit of a local attraction—people would drop by just to see what was new on the wall.

One of the regulars at our home was Henrik Igityan, a remarkable figure in Armenia. He founded the world’s first Children’s Art Museum, showcasing art by kids from all over the world. He also established the Museum of Modern Art in Yerevan and ran schools of aesthetic education. You could study anything there—sculpture, ceramics, painting, dance—you name it. He spent a lot of time with us, keeping an eye on my work and encouraging me in what I was doing. When I was ten, Igityan organized my first exhibition in Yerevan. The show then traveled—half of it went to Spain, the other half toured American cities. By eleven or twelve, I had exhibitions in Moscow and St. Petersburg, each showing over a hundred works. When I was fourteen, he set up my first solo show in New York.

You mentioned that you started painting at five. How did it all begin? Was there something specific that inspired you, or was it more about the creative atmosphere in your family?

We had a huge collection of art books at home, and I was always looking through them—especially those on the Renaissance and the Dutch masters. I wanted to create work like that. I started drawing with pencils, but it was frustrating. I’d look at Rembrandt’s paintings and think, “Why do his colors have such depth, while mine are just green, yellow, and red scribbles?” My dad explained that they painted with oil, in layers. I said I wanted to do the same, so he went out and bought me a big box of oil paints. The moment I tried them, that was it—that became my world.

Do you remember that feeling of painting with oils for the first time?

My parents told me that when my dad bought the paints, he left them for me and went to work. He planned to teach me how to mix colors in the evening, but when he got home, I’d already finished ten paintings. For me, it felt completely natural. The colors were like a game. I remember mixing them, discovering what worked together and what didn’t, which pigments were stronger. It was like a battle—black would "conquer" yellow, and strong shades would overpower weaker ones. My canvas was a playground, and it was all just part of the fun.

You studied in Yerevan and later in Switzerland. How did your formal education impact what you do now?

For me, school was more about figuring out what didn’t interest me. In Armenia, it was a classic post-socialist education, a weaker reflection of the St. Petersburg Academy. Most of our teachers were over seventy. When they said I was doing something “too modern,” they’d compare me to Picasso. I’d joke that Picasso died before I was born.

In Switzerland, it was the opposite—super modern. When I sat down to paint on canvas with oils, the teachers were shocked. Using a brush and oil paints felt almost like an insult to them. At the time, I didn’t handle it well. I became defensive and tried to prove myself. But I also started experimenting. That’s where I got into video art and photography.

School in Switzerland was a space for experimentation—a place where I had the right to make mistakes. That’s the biggest positive takeaway for me: the freedom to try, fail, and learn. As a student, no one could really criticize your mistakes. But once you graduate and become a full-time artist, every step is on you.

Could you share about your current projects and plans? What are you working on now?

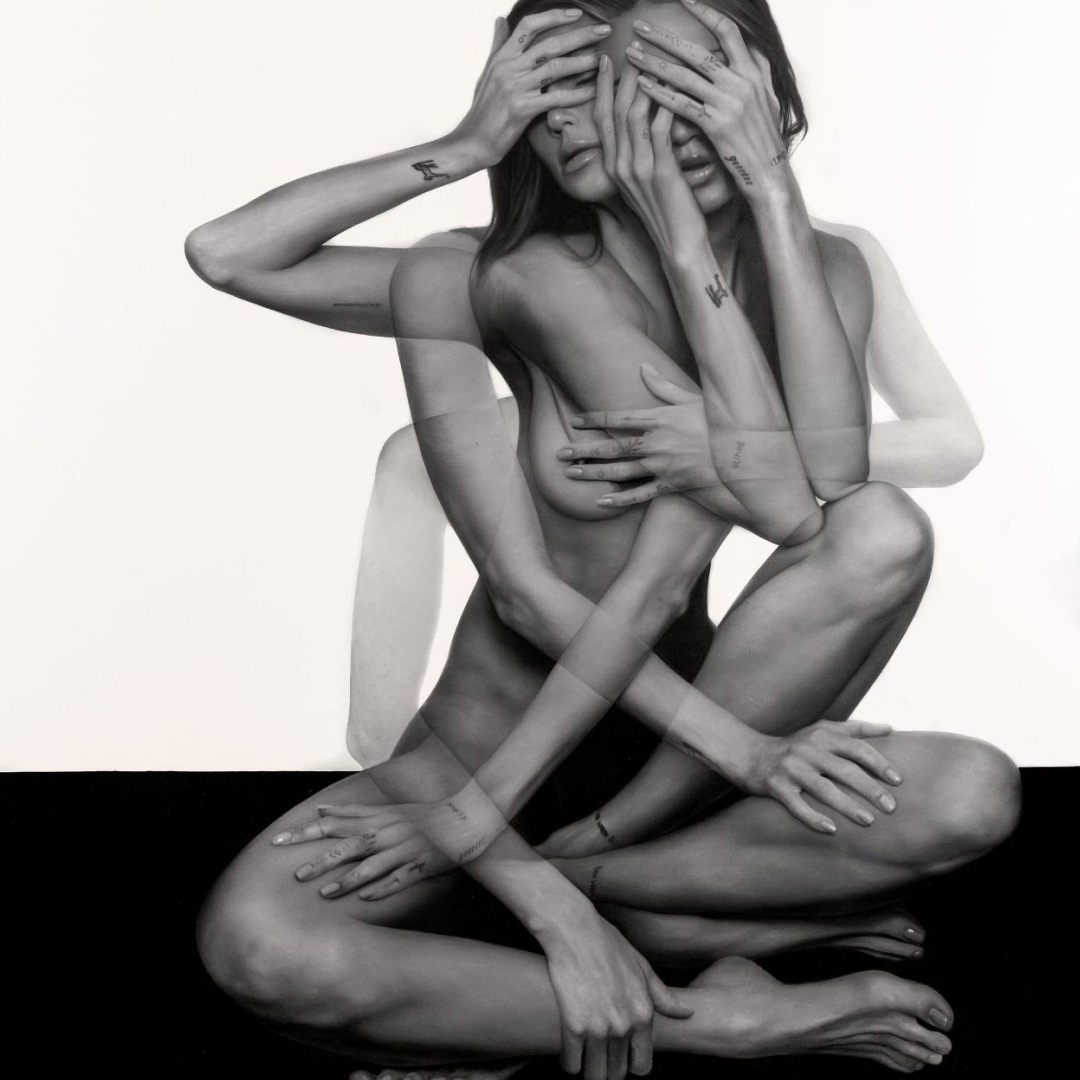

I currently have an exhibition at the Armenian Museum of America in Boston. It’s been running since September and will close on March 9th, so most of my work is there. I’m finishing the last pieces for my self-isolation series and already starting a new one. This new series will be an evolution of my previous work, but I’m moving away from realism. I want to create more freely, without models or references, and explore a more abstract approach. I’m also experimenting with a new color series. I haven’t shown it to anyone yet, but I’m excited to dive back into working with color.

Interview by Inna Logunova

Photo courtesy of Tigran Tsitoghdzyan