Stanislava Malakhovskaya is a versatile contemporary artist working in printing techniques. Coming from a family of famous avant-garde artists, Nathan Altman and Bronislav Malakhovsky, she grew up amid their works, which influenced her greatly. Her latest exhibition, "Graphics 3.0," is on view until August 4 at the mArs Gallery in Saint Petersburg, situated next to the building that housed the first private art gallery in the Russian Empire. This historic location hosted the first exhibitions of then-little-known artists Nathan Altman, Marc Chagall, and Kazimir Malevich. It was also where Malevich's "Black Square" was first shown, causing a scandal.

Fine Art Shippers spoke with Stanislava Malakhovskaya about her creative approach, way of blending abstract and figurative art, research of family archives, and a recent book published in New York.

Artist Talk: Stanislava Malakhovskaya on Art as Meditation

You work with etching, lithography, and ink drawing with Chinese brushes. What drew you to these techniques, and what do you find particularly appealing about them?

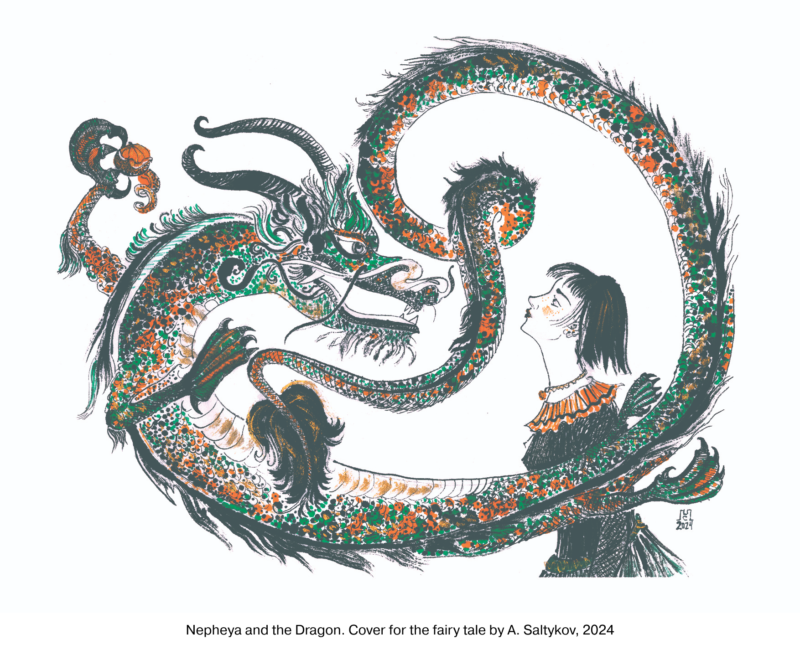

Stanislava Malakhovskaya: I have always preferred graphics to other forms of art, largely thanks to my great-grandfathers, Nathan Altman and Bronislav Malakhovsky. Altman was a versatile artist, both a painter and sculptor. My other great-grandfather, Bronislav Malakhovsky, specialized in magazine and book illustrations. Growing up in a house filled with graphics, I was constantly exposed to this art form, which shaped my taste and oriented me toward graphics as a means of artistic expression. That's why I went to study at the Stieglitz Academy's Department of Book and Easel Graphics. There, I learned various manual printing techniques such as lithography, etching, and linocut. I am captivated by the tactile interaction with materials—the textures of paper or stone, and the use of brushes, special chalk, or scalpels to remove excess paint. This experience is vastly different from drawing with a stylus and tablet, where the sensation remains constant regardless of what you create.  Do you lean more towards figurative or abstract art? I have always been interested in formal explorations and the discoveries of the avant-garde. In addition to the Academy, I studied at Gennady Zubkov's Studio for two years, where I was trained in the system of the State Institute of Artistic Culture (GInKhUK), organized by Kazimir Malevich in the 1920s. We studied Impressionism, Cézannism, analytical and synthetic forms of Cubism, Suprematism, and Vladimir Sterligov’s bowl-dome system. These studies greatly influenced me. As a result, my work blends figurative and abstract art. I am also greatly inspired by the informal art of Leningrad. I know many prominent artists in this movement personally, and I attended their exhibitions from a young age. Creative process. How long do you spend developing the concept, and how long do you work on the execution itself? I spend a long time thinking and work very quickly. I can spend several months developing a concept, producing dozens of sketches and variations. I also practice calligraphy, though not in the Japanese or Chinese styles typically associated with it, but in Russian and European styles. Calligraphy taught me to be super concentrated in the moment, and I now use this approach for all my work. My drawings are almost like a single line, close to abstraction, with expressive silhouettes and shapes, and very concise. Technically, they are done quickly, but I take a long time to focus and draw that one perfect line. You are also a musician, engaging in ethnic music. What attracts you to this genre? Music has always been a part of my life. My uncle is a rock musician, and he got me hooked when I was 13 years old. I started playing the Celtic harp at 20, which is quite late. Despite this, I managed to master it at a professional level and even trained on the classical harp. Ethnic music attracts me because it helps me enter a trance-like state, a form of meditation, which is the same state from which I create my graphic works. It's all closely related. Other types of music don’t provide the same immersion or feeling. I am fascinated by exploring and finding very ancient melodies, creating my own arrangements for them, or composing stylized melodies.

Do you lean more towards figurative or abstract art? I have always been interested in formal explorations and the discoveries of the avant-garde. In addition to the Academy, I studied at Gennady Zubkov's Studio for two years, where I was trained in the system of the State Institute of Artistic Culture (GInKhUK), organized by Kazimir Malevich in the 1920s. We studied Impressionism, Cézannism, analytical and synthetic forms of Cubism, Suprematism, and Vladimir Sterligov’s bowl-dome system. These studies greatly influenced me. As a result, my work blends figurative and abstract art. I am also greatly inspired by the informal art of Leningrad. I know many prominent artists in this movement personally, and I attended their exhibitions from a young age. Creative process. How long do you spend developing the concept, and how long do you work on the execution itself? I spend a long time thinking and work very quickly. I can spend several months developing a concept, producing dozens of sketches and variations. I also practice calligraphy, though not in the Japanese or Chinese styles typically associated with it, but in Russian and European styles. Calligraphy taught me to be super concentrated in the moment, and I now use this approach for all my work. My drawings are almost like a single line, close to abstraction, with expressive silhouettes and shapes, and very concise. Technically, they are done quickly, but I take a long time to focus and draw that one perfect line. You are also a musician, engaging in ethnic music. What attracts you to this genre? Music has always been a part of my life. My uncle is a rock musician, and he got me hooked when I was 13 years old. I started playing the Celtic harp at 20, which is quite late. Despite this, I managed to master it at a professional level and even trained on the classical harp. Ethnic music attracts me because it helps me enter a trance-like state, a form of meditation, which is the same state from which I create my graphic works. It's all closely related. Other types of music don’t provide the same immersion or feeling. I am fascinated by exploring and finding very ancient melodies, creating my own arrangements for them, or composing stylized melodies.  Where do you find ancient melodies? I find some melodies on the internet and read research by musicologists. I also have an international circle of friends who contribute. For example, I have friends in Armenia. With my ensemble, “Mama Nature Band,” we recently made several arrangements of old Armenian songs, which are so beautiful. Our ensemble includes vocals, percussion, and various ethnic instruments like the Hang, which is very popular in modern ethnic music, bansuri flute, as well as string instruments like the djuras, baglamas, and tar. We also use unique instruments like the crystal harp and crystalophone, which one of our members, an engineer and musician, designs and makes from quartz. I know you are researching your family archives related to Nathan Altman and Bronislav Malakhovsky. How long ago did you start this work? Going into art history or archiving wasn't part of my original life plans. While my grandparents were alive, they kept everything to themselves—there were no exhibitions or articles, and we didn't even know exactly what was there. In 2018, I was approached to write an article about my great-grandfathers, Nathan Altman and Bronislav Malakhovsky, given their notable contributions. I realized I didn't know how to do it properly. With some guidance, I completed the article, which was published in the “Connaisseur” almanac, dedicated to unpublished archives, and it was well-received. This experience motivated me to study the archive professionally. I decided to pursue further education and enrolled in the Repin Academy of Arts, majoring in art history. Now, I'm a PhD student working on a dissertation about Nathan Altman's graphics.

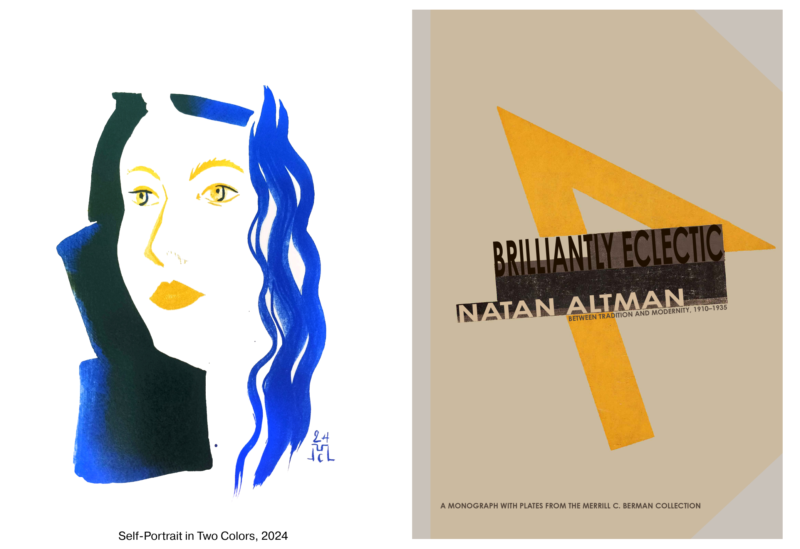

Where do you find ancient melodies? I find some melodies on the internet and read research by musicologists. I also have an international circle of friends who contribute. For example, I have friends in Armenia. With my ensemble, “Mama Nature Band,” we recently made several arrangements of old Armenian songs, which are so beautiful. Our ensemble includes vocals, percussion, and various ethnic instruments like the Hang, which is very popular in modern ethnic music, bansuri flute, as well as string instruments like the djuras, baglamas, and tar. We also use unique instruments like the crystal harp and crystalophone, which one of our members, an engineer and musician, designs and makes from quartz. I know you are researching your family archives related to Nathan Altman and Bronislav Malakhovsky. How long ago did you start this work? Going into art history or archiving wasn't part of my original life plans. While my grandparents were alive, they kept everything to themselves—there were no exhibitions or articles, and we didn't even know exactly what was there. In 2018, I was approached to write an article about my great-grandfathers, Nathan Altman and Bronislav Malakhovsky, given their notable contributions. I realized I didn't know how to do it properly. With some guidance, I completed the article, which was published in the “Connaisseur” almanac, dedicated to unpublished archives, and it was well-received. This experience motivated me to study the archive professionally. I decided to pursue further education and enrolled in the Repin Academy of Arts, majoring in art history. Now, I'm a PhD student working on a dissertation about Nathan Altman's graphics.  What is the focus of your research? One of my main goals has been to create a comprehensive catalog of Altman's works, as there are many forgeries on the market. Collectors and museum professionals often struggle to determine the authenticity of pieces. Although this project is still ongoing, some of the work has been completed, and part of my catalog, “A Summary of Altman's Book Graphics,” was published in New York in 2022. It is the first English-language monograph on Altman's graphic works up to 1935. I worked on it together with Alla Rosenfeld, a Russian-American art historian who has lived in America for 35 years. It was such an inspiring experience. This book is available in many American libraries, and I receive positive feedback about it. What do you find most rewarding in your research on Nathan Altman? When I first started, I didn't expect such a strong response to my work and the widespread interest in it worldwide. I share my articles and findings and manage social media groups dedicated to Altman's work. Researchers from around the world contact me with questions, and I help them as much as I can. This is truly rewarding.

What is the focus of your research? One of my main goals has been to create a comprehensive catalog of Altman's works, as there are many forgeries on the market. Collectors and museum professionals often struggle to determine the authenticity of pieces. Although this project is still ongoing, some of the work has been completed, and part of my catalog, “A Summary of Altman's Book Graphics,” was published in New York in 2022. It is the first English-language monograph on Altman's graphic works up to 1935. I worked on it together with Alla Rosenfeld, a Russian-American art historian who has lived in America for 35 years. It was such an inspiring experience. This book is available in many American libraries, and I receive positive feedback about it. What do you find most rewarding in your research on Nathan Altman? When I first started, I didn't expect such a strong response to my work and the widespread interest in it worldwide. I share my articles and findings and manage social media groups dedicated to Altman's work. Researchers from around the world contact me with questions, and I help them as much as I can. This is truly rewarding.

Interview by Inna Logunova Photo courtesy of Stanislava Malakhovskaya