It promotes its artists through gallery collaborations, a lending program, digital media, sponsorships, prizes, and partnerships with institutions.

In this conversation with Fine Art Shippers, Shay Benamram, collection manager at Africa First, discusses the history of the collection, the place of African art in the global art scene, and shares some memorable moments from his work.

Africa First was founded in 2017, though Serge Tiroche began his journey as a collector earlier. What inspired him to build this particular collection?

Shay Benamram: Indeed, Serge began collecting art more than thirty years ago, starting with Israeli art. Africa First came later as a separate collection of contemporary African artists. What makes Africa First special is that it supports young, up-and-coming artists, some are just out of art school. Serge usually discovers them online, on Instagram and other platforms. If he sees something that excites him, he reaches out, and from there, a collector-artist relationship begins.

He has also traveled to Africa several times, which has helped him understand the art scene and the market better, and connect with artists personally. Eventually, the project grew to include a residency program, where African artists were invited to Israel to live and work.

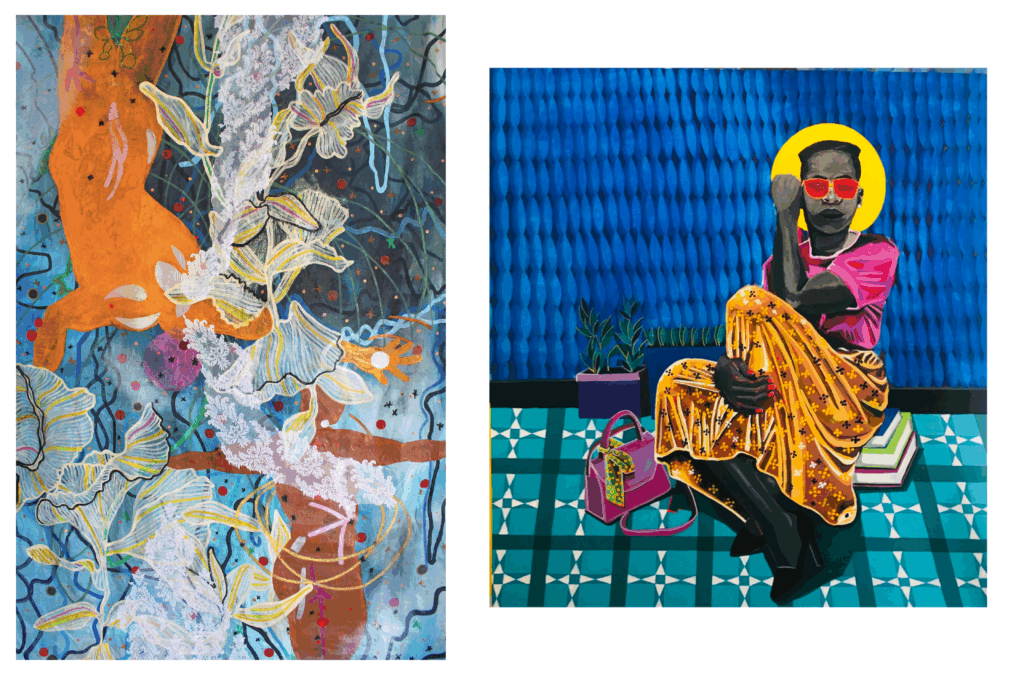

Tiffanie Delune. Rivers Never Meet Twice the Same Way, 2021 Tafadzwa Tega. Sister Mary, 2020

What motivated him to collect African art? Was it something personal, or did he also want to help raise awareness of underrepresented artists?

I think it was a combination of both. On a personal level, Serge was genuinely drawn to African art, its visual language, aesthetics, and materiality. At the same time, he was also motivated by a sense of purpose. He understood that many African artists struggle to gain international visibility. So while his interest began with appreciation, it quickly turned into a commitment to support emerging talent from the continent.

Speaking of the Israeli public. How has the audience responded to African art? Has it always had a presence here, or was it something new?

It was definitely something new for most people. Before Africa First, African art wasn’t widely shown in Israel. You might occasionally come across a piece in a group exhibition, but that was about it. So when we began presenting it more consistently, especially through our shows at Gordon Gallery, the response was incredible.

Does the collection focus on any specific topics, such as gender, ecology, or the African diaspora, or is it more about the individual artists?

There isn’t one unifying theme, but geography and local narratives definitely play an important role. The artists in the collection come from a wide range of cultural and social backgrounds across Africa. Each one brings their story, shaped by their own political and social context. So I’d say the collection is more about capturing a diverse range of voices and perspectives.

You mentioned your residency program. Can you tell us more about how it started?

It actually began even before Africa First was officially launched. In 2016, Serge invited two African artists to Israel, and that experience sparked the idea for the residency. From there, it grew into a more regular program. Each year, we hosted a new artist.

In 2022, after a pause during the pandemic, we welcomed Simphiwe Mbunyuza, a ceramic artist from South Africa. He spent three months with us, and the residency concluded with a beautiful solo show at the African Studies Gallery in Tel Aviv. It was a very special moment.

Let’s talk about African art itself. Are there certain trends or approaches you observe in how African artists are using visual language today?

What stands out most is the incredible variety of mediums artists are working with. Some use very traditional forms, like ceramics or sculpture, but interpret them in highly personal ways. For instance, we hosted a South African artist named Simphiwe Mbunyuza through our residency program. He works with ceramics, but not in the classical sense. He uses the medium to tell stories from his heritage, blending symbols and textures that reference his village and community. The pieces almost look like fabric, they’re very tactile. Then there are artists like Treasure Mlima, who works across both digital and traditional media. He creates images with software and then transfers them onto wood through etching. And beyond the materials, many artists are exploring themes like decolonization, identity, and community. Their work is often rooted in personal experience and speaks to broader cultural or political questions.

How do African artists address colonial history? In the West, these conversations often carry a sense of guilt or a need to make amends. But what about the artists themselves, who live with the legacy of that history?

That’s a really important question. From what I’ve observed, many artists approach these themes in personal ways. Much of the work reflects social and political realities. You’ll find pieces that speak to inequality, identity, or the lasting impact of colonialism. But it’s rarely just about looking back.

Some artists explore these ideas through fashion, not just as style, but as a symbol. They might draw on Western aesthetics to comment on cultural influence or globalization. Beneath the surface, though, they’re often grappling with deeper questions, like the power dynamics between Africa and the West, or the need to reclaim control over their own narratives.

Are global institutions responding to this? Have you seen more interest in African art from biennials, museums, or collectors in recent years?

Absolutely, there’s been a real shift, it’s no longer viewed as something niche. There’s been a noticeable rise in the presence of African art across European galleries, with many now including artists of African descent in their main rosters. Phillips shows a fair amount of African art as well, although they don’t have a dedicated sale for it.

What about the art scene on the continent itself? What’s happening with local institutions, galleries, and collectors?

There’s a lot of exciting growth happening. One standout is Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, which has become one of the leading contemporary art museums in Africa. But beyond that, we’re seeing a steady rise in strong galleries opening across Ghana, as well as in South and North Africa. What’s especially encouraging is that these galleries aren’t just showing work locally, they’re very active on the international art market. It’s a vibrant and fast-growing scene, and it’s incredibly rewarding to be part of it.

I assume, as the collection manager, you’ve had some memorable moments while working with it. Could you share one?

Oh, there have been so many. I remember a small moment that still makes me smile. My name, Shay, means “gift” in Hebrew. One day, Simphiwe, the artist who joined us through the residency, mentioned that his name also means “gift” in his language. We both laughed, saying we were “both gifts,” as he put it. It was a nice reminder that, above all, art and our life in general are all about human connection.

Interview by Inna Logunova

Photo courtesy of Africa First