New York-based Scarpini Studio specializes in the conservation and restoration of Old Masters, 19th-century, modern, and contemporary paintings.

Fine Art Shippers recently spoke with the company’s founder, Maria Scarpini, to discuss the principles of scientific restoration, the differences between European and American approaches, and her most memorable experiences as a conservator and restorer.

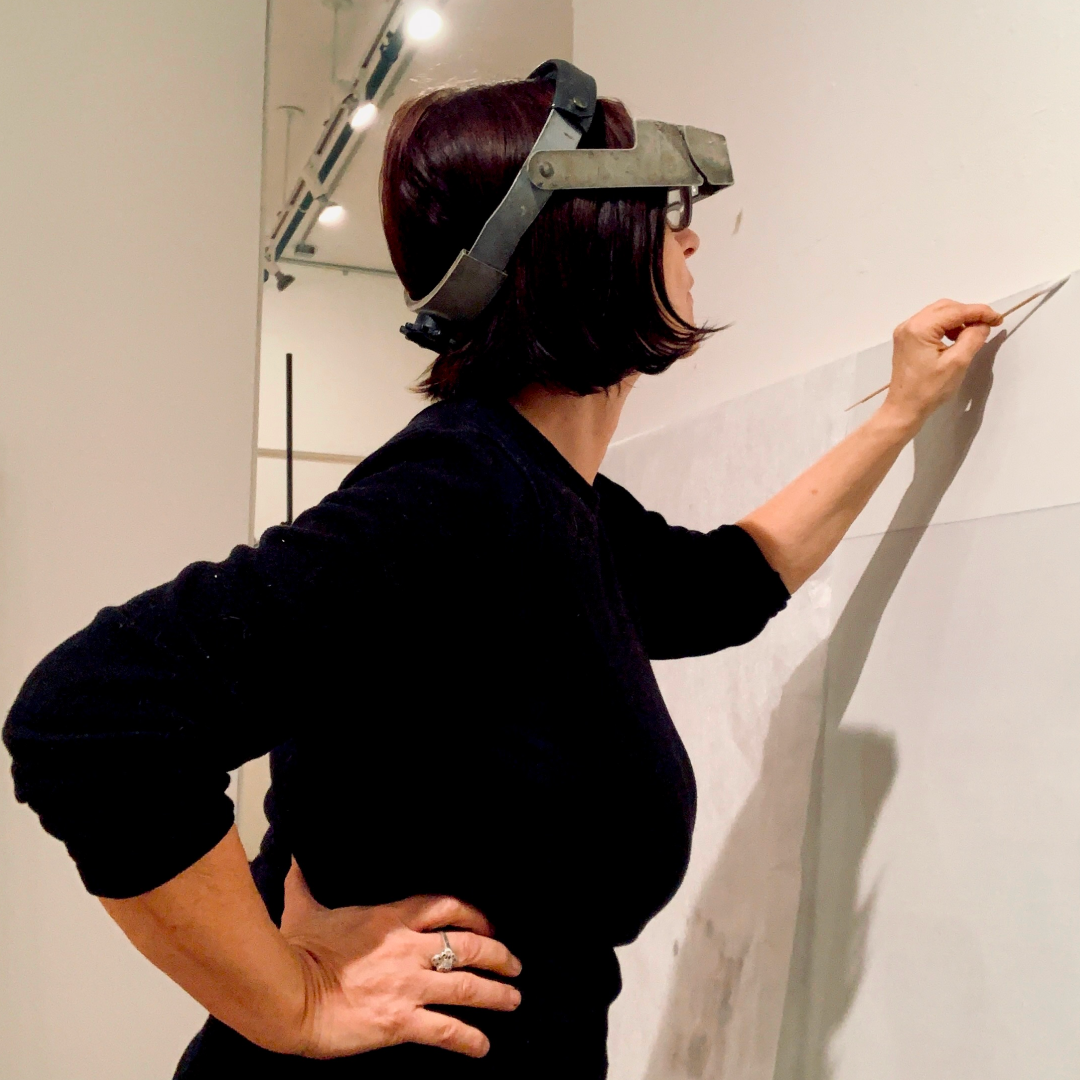

Scarpini Studio: The Delicate Art of Painting Restoration

You’re originally from Italy and had a successful career there. What motivated you to relocate to the United States?

Maria Scarpini: I moved to the U.S. at 36, after gaining substantial experience in art conservation in Italy. My journey began in Milano, led me to study in Florence, and eventually to Rome, where I worked on Old Masters, archaeological artifacts, and frescoes. I returned to Milano and worked on contemporary art, including restoring paintings damaged by a mafia bomb at the Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea.

My decision to leave Italy was driven by a sense of stagnation. Despite Italy’s rich art history, the conservation field was fraught with economic difficulties and bureaucratic hurdles. Relocating to New York was a turning point. I had a friend here and seized an internship opportunity at the Museum of Modern Art. This move allowed me to collaborate with a talented conservator and, in 2003, I established my own business.

Let’s talk about the key principles of restoration in regard to Scarpini Studio’s specialization— Old Masters and 19th-century paintings.

Paintings can be executed either on canvas or on wood panels, plaster, and walls. Historically in Italy, before the advent of canvas, paintings were commonly done on wood panels, sized with animal glue-based gesso, and painted using egg tempera. The introduction of oil painting from Northern Europe towards the end of the 15th century marked first a shift in medium, oil, and then towards a new support, the canvas, which was appreciated for its portability.

In canvas paintings, the structure comprises the canvas itself, a wooden stretcher on which the canvas is mounted, a ground layer applied to the canvas, and the paint layer. Damage can manifest at any of these levels: the paint may detach from the ground layer, the ground layers might separate from the canvas, or mechanical accidents may cause the canvas to tear. Such damage often stems from aging or environmental factors, such as humidity, which can affect the canvas and lead to cracking or craquelure. Accidental damage, like dropping a painting, is another common issue.

Restoration philosophies have significantly evolved over time. For example, in the 18th and 19th centuries, restorers frequently overpainted artworks to make them conform to contemporary aesthetic preferences. By the mid-20th century, the emphasis shifted towards preserving the artist’s original intent and restoring the material itself. A major contemporary challenge in conservation is addressing these additional and non-original layers of paint, which were applied in the past to “modernize” the artworks.

Could you elaborate on the contemporary approach to restoration?

There are differences in the aesthetic aspects of restoration, especially in retouching techniques, between the U.S. and Europe. In both European and American traditions, the foremost objective is to preserve the artist’s original intent while ensuring that any restorative interventions are reversible. This strategy enables future conservators to implement new techniques or revise existing treatments as needed.

However, In Italy, the visual part of the restoration, called integration of losses is conducted in a more conservative way, where sometimes a neutral tone is used, as opposed to a full integration of the losses with the surrounding colors. The idea is to allow the ”neutralized” loss to recede in the background and let the image emerge in the foreground. In addition, the restoration is supposed to be clearly recognizable as a modern restoration upon close inspection, while disappearing at a distance. When I arrived in the United States, I encountered a different philosophy, where restorations aim to be completely invisible. However, the trend in Europe is gradually shifting towards adopting the less visible restoration methods that are common in America.

You mentioned dealing with multiple historical layers in a painting during the restoration process. Do you employ special techniques, like X-ray imaging, to reveal these layers?

As a private conservator, my resources are more limited compared to those of big museums. While museums can use advanced technologies to examine the different layers of a painting, my approach in private practice is more hands-on and empirical.

One tool I do use is UV light, which helps in identifying different layers of a painting. In a dark room, under UV light, varnish emits a greenish-yellow hue, while later retouchings appear darker and more opaque. This technique is helpful in differentiating between the original layers and those added later.

I’m curious about some of your most memorable experiences in restoration and conservation. Can you share a few examples?

One of my most profound experiences was restoring frescoes in Italy, in diverse locations like churches, museums, and palaces. A particularly memorable project was on the Colonna Antonina an ancient column in Rome dating back to around 190 AD. The experience of working on this archaeological treasure and collaborating with a large team across different seasons was unforgettable. I also had the opportunity to work briefly on the late 15th-century frescoes by Luca Signorelli in the Cappella di San Brizio in Orvieto.

In the U.S., a notable experience was at the Guggenheim Museum, where I contributed to the restoration of a contemporary sculpture by Bruce Nauman. This sculpture, composed of about 35 sandstone pieces, posed a significant challenge from a restorer’s perspective: glue from packing tape had penetrated the stone, and I had to carefully remove it without damaging the artwork. The opportunity to work on such a significant piece by a renowned artist at a prestigious institution was a significant step in my career.

Interview by Inna Logunova

Photo courtesy of Scarpini Studio